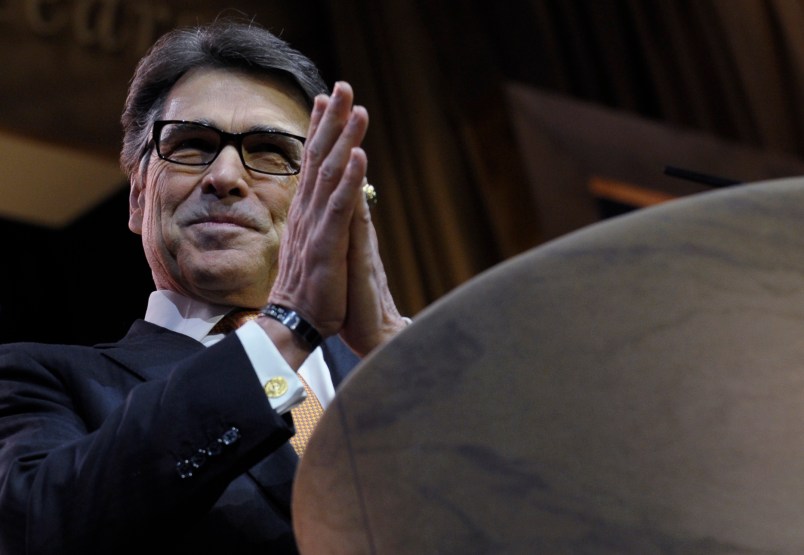

Rick Perry’s special prosecutor is going to have a hard time taking him down.

The Texas governor was indicted by a grand jury Friday on one count of abuse of power by intentionally misusing government property to harm someone, and one count of coercion of a public servant. He insists he’s innocent and calls the indictment a politically-motivated “farce” that’s likelier to occur in the “old Soviet Union” than the United States.

The charges spring from the Republican governor’s veto of funds for the office of Travis County District Attorney Rosemary Lehmberg, a Democrat, after she was arrested in 2013 for drunk driving — she served about half of her 45-day prison sentence before returning to work. Perry said she has lost the public’s trust and threatened to veto the funds unless she resigned; she refused, and he nixed a $7.5 million appropriation for her office in the state budget.

Susan Klein, a professor at UT-Austin School of Law, torched the indictment.

“I think the Perry indictment is tragic. It makes my beloved city of Austin a national laughingstock. I am embarrassed to be a liberal Democrat. I consider Perry’s behavior ungentlemanly but certainly not illegal,” she told TPM. “I see nothing in the indictment that would lead me to believe there is anything for the government to prove. I think the statutes were designed to prevent bribery, extortion or fraud, not use of the Governor’s veto authority.”

Many legal experts say the case against Perry is weak. Would a grand jury really send a governor to jail for exercising his veto power? The two-page indictment is vague and leaves many questions unanswered about what the grand jury was told and what legal avenues the prosecution intends to pursue.

Legal experts raise three big problems with convicting Perry, a task that’ll fall to special prosecutor Michael McCrum, who was tapped by a Republican-appointed state judge.

Travis County District Attorney Rosemary Lehmberg speaks during an interview in her Austin, Texas, office. (AP)

1. The statutory problem

The first count of the indictment says Perry “intentionally or knowingly misused government property” to harm Lehmberg. The “government property” in question appears to be the $7.5 million in biennial funds for the Travis County DA’s Public Integrity Unit (PIU), which she ran.

Eugene Volokh, a professor at UCLA School of Law, pointed out that the Texas statute cited says the funds have to be in “the public servant’s custody or possession” in order to be “misuse[d].” But Perry never actually had the funds in his possession; he vetoed them before they were legally appropriated. And even if they were appropriated, the funds would arguably be in legal possession of the PIU, not the governor’s office.

“I don’t see how this can possibly apply to Perry’s behavior,” Volokh concluded.

One theory the prosecution may conceivably pursue, lawyers speculate, is that the funds were in Perry’s “custody or possession” between the time they passed the legislature and his veto. But the indictment provides few clues.

“On the more serious charge, the abuse of official authority, I really am not sure what the theory is,” said Jennifer Laurin, a professor at UT-Austin School of Law. “It’s hard to know, looking at the indictment, what the state might be seeking to prove.”

Texas Gov. Rick Perry’s legal defense team address reporters during a media briefing held Monday, Aug. 18, 2014 at the Stephen F. Austin Intercontinental Hotel. (AP)

2. The constitutional problem

The second count of the indictment charges that Perry “intentionally or knowingly influenced or attempted to influence Rosemary Lehmberg.” The theory is that he tried to coerce her to step down by threatening to hollow out funds for her office; if she resigned he’d have appointed her successor.

It is conceivable that Perry did violate the text of the relevant Texas statute by publicly threatening to veto the funds (nobody doubts he had the legal authority to carry out the actual veto). The problem is that the allegation suggests Perry broke the law by speaking, in which case the law criminalizes speech, and is likelier to be be ruled unconstitutional, said Rick Hasen, a professor at UC-Irvine School of Law.

“The statute may be unconstitutionally vague or overly broad and thus it might violate the First Amendment,” Hasen said. “If he didn’t say anything and just vetoed it then there would be no question [of illegality].”

Jonathan Turley, a professor at George Washington University School of Law, said that if Perry’s actions make him a criminal, “a wide array of official actions and public comments could be criminalized.”

The American flag and Texas state flag are carried during the 65th annual Jaycees Independence Day parade, Friday, July 4, 2014, in Odessa, Texas. (AP)

The American flag and Texas state flag are carried during the 65th annual Jaycees Independence Day parade, Friday, July 4, 2014, in Odessa, Texas. (AP)

3. The obstruction of justice problem

The other challenge for the prosecution is that even if they find evidence that Perry used his veto power to shut down a serious PIU investigation of him or one of his allies, it’s not clear that would be covered under the existing indictment.

According to reports, Perry’s appointees at the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas were being investigated by Lehmberg’s PIU, and the governor’s opponents charge that he used his veto power to try and shut that probe down. Perry strenuously denies that the PIU’s investigations had anything to do with his veto threat. If there’s evidence to the contrary, that would make for a stronger case against him.

But even then, legal experts say that charge sounds more like obstruction of justice, which is not being alleged here and may require a new indictment.

“If there’s a charge of obstruction of justice … that’d be different. But that’s not what’s being alleged,” Hasen said. “I presume he’d have to be indicted again on such charges.”

Laurin of UT-Austin also wondered what the prosecution’s strategy was.

“I’m not sure why they chose these charges and not others,” she said.

Let his trial begin. No one is above the law.

I don’t much care whether the governor is convicted or not convicted though I am stocking up on popcorn for the proceedings. Just bound to be …interesting. I just don’t want this Texas dimwit to be elected President of the United States of America, is my only interest in the case. We already had one Texas dimwit in the White House and that didn’t go so well, did it?

What is endlessly annoying to me personally though, is all of these pundits and journalists – without any knowledge of Texas law or any legal background whatsoever, to think they have to pull opinions out of their ass about the legal merits of the case. Jonathan Chait, for example, sez (paraphrase) “Well I read the indictment TWICE and can’t see any legal basis for it.” And he was widely quoted throughout the liberal blogos for this sage opinion. :::EYEROLL::::

I guess the Republican special prosecutor appointed by a Republican administration who was thought to be too beholden to Texas Republican interests to be named for the position, thinks there might be a case. With all due respect to all the California academics whose opinions were featured in this particular piece.

Well, you know something, Jonathan? You gotta start somewhere!

IMHO,Mr Turley use to be “fair and balanced” not anymore,You use to see him quite a bit being a go to guy on MSNBC especially when Keith Olberman was on.Not anymore he seems to have taken up a cause against the President,IMHO.

“The problem is that the allegation suggests Perry broke the law by speaking, in which case the law criminalizes speech…”

Blackmail and extortion can also sometimes serve as examples of speech being criminalized, no?