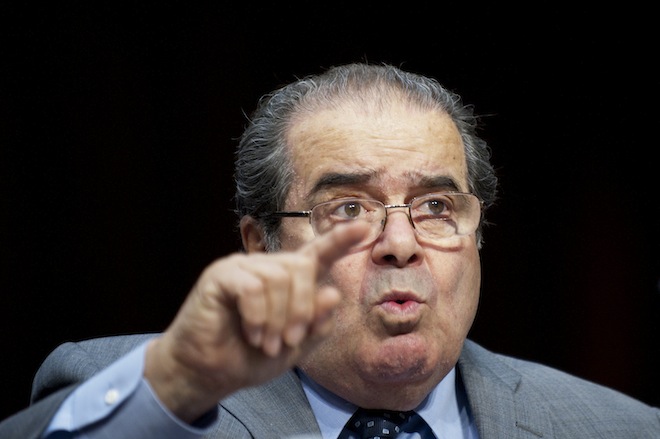

Will the Supreme Court rule in favor of marriage equality when it takes up the Defense of Marriage Act next spring? One justice warned nearly a decade ago that the Court had already paved the way to do just that: Antonin Scalia.

In a landmark 2003 decision, the Court ruled that states may not outlaw sodomy among consenting adults of the same sex. The minority dissent in the 6-3 ruling in Lawrence v. Texas was authored by Justice Scalia, who argued that the Court’s reasoning effectively, if not explicitly, knocked down the legal basis for outlawing gay marriage.

“Today’s opinion dismantles the structure of constitutional law that has permitted a distinction to be made between heterosexual and homosexual unions, insofar as formal recognition in marriage is concerned,” Scalia wrote.

Justice Anthony Kennedy’s majority opinion said the Court’s ruling against anti-sodomy laws “does not involve whether the government must give formal recognition to any relationship that homosexual persons seek to enter.”

Scalia’s retort: “Do not believe it.”

“This case ‘does not involve’ the issue of homosexual marriage only if one entertains the belief that principle and logic have nothing to do with the decisions of this Court,” he wrote.

The Reagan-appointed justice accused the majority on the Court of having “taken sides in the culture war” and having signed on to the “homosexual agenda.”

“The people may feel that their disapprobation of homosexual conduct is strong enough to disallow homosexual marriage, but not strong enough to criminalize private homosexual acts — and may legislate accordingly,” Scalia wrote. “The Court today pretends that it possesses a similar freedom of action, so that that we need not fear judicial imposition of homosexual marriage.”

Ten years later, public opinion has shifted dramatically in support of marriage equality. And next spring the Supreme Court will consider whether or not the Defense of Marriage Act — the 1996 law that prohibits federal recognition of same sex marriage — also violates the Constitution’s guarantee of equal protection. Two federal appeals courts have ruled that it does.

Scalia, in his 2003 Lawrence v. Texas dissent, sought to counter the majority’s decree that outlawing gay sex serves no legitimate state interest, in part by warning: “This reasoning leaves on pretty shaky grounds state laws limiting marriage to opposite-sex couples.”

On that matter, supporters of marriage equality can only hope Scalia was exactly right.