As concerns escalate over the GOP’s plans to repeal Obamacare, and what it means for the millions with pre-existing conditions whose coverage has been guaranteed by the law, Republicans have pointed to so-called high-risk pools, as if they were magic bullet of sorts for covering seriously sick individuals.

However, using high-risk pools as a substitute for the Affordable Care Act would cost a boatload of money, health care policy experts tell TPM, and when states implemented it in the past, it was often consumers who were left picking up the tab or left out of the system entirely.

“It’s better than nothing, to help some people,” said Henry Aaron, a senior fellow in the Economic Studies Program at the Brookings Institution, “but it’s a massive step backward from the Affordable Care Act.

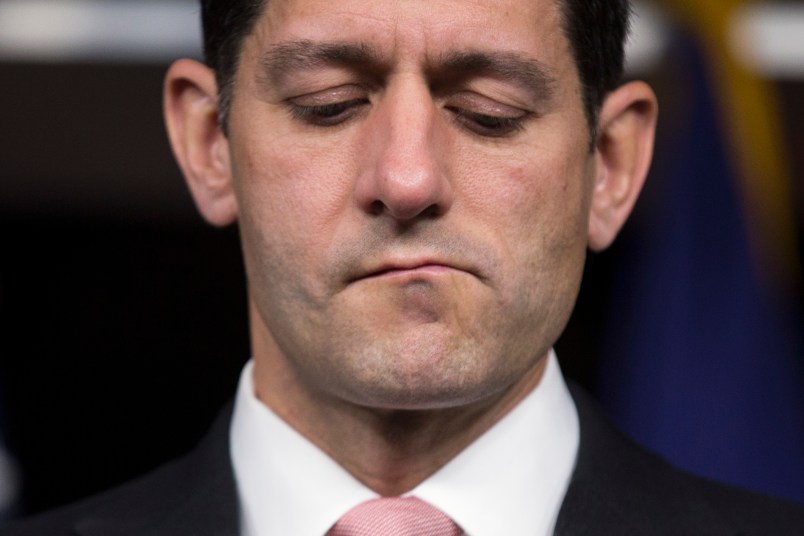

Speaker Paul Ryan (R-WI) was pushing the idea again at a recent CNN town hall for his favored idea of protecting consumers with pre-existing conditions after an Obamacare repeal by creating what’s known as high risk-pools. The theory is that people who have the sort conditions that are the most expensive to cover — and who, before the Affordable Care Act, were discriminated against by insurers — are siphoned off from the rest of the individual market, to keep premiums low for healthy people. The proposal was in Ryan’s “Better Way,” a rough outline of ACA replacement ideas House Republicans offered last year, as well as the proposals of Rep. Tom Price (R-GA) and Senate Finance Chair Orrin Hatch (R-UT), making it a mainstay of GOP health care alternatives.

But the system comes with some serious downsides, health care experts told TPM, and the kinds of coverage states offered with their own risk pools before the ACA are by no means equivalent to the coverage pre-existing condition enrollees have gotten through Obamacare, nor did the state pools account for the millions whose coverage would be at a risk with repeal.

“A high-risk pool is not an appropriate substitute,” said Linda Blumberg, a senior fellow in the Health Policy Center at the Urban Institute. “It’s not an equivalent in anyway for making sure that people with pre-existing conditions have adequate affordable coverage on an ongoing basis, unless the federal government was willing to invest an enormous amount of dollars into making it work.”

Ryan explained on CNN that idea was to allow taxpayers to “finance the coverage for those eight percent of Americans under 65” who have pre-existing conditions like cancer and other serious ailments, while you “dramatically lower the price for the other 92 percent of Americans.” But the math is not quite that simple.

According to the Department of Health and Human Services, at least 23 percent of Americans have types of conditions that would have made them eligible for a state high risk pool before the Affordable Care Act, and even more (51 percent of Americans) have more broadly the kinds of conditions insurers would use as a basis for blocking coverage. A Kaiser analysis estimated that 27 percent of American adults have the types of conditions that would make them uninsurable in the individual market before the Affordable Care Act. (The HHS and Kaiser numbers above are for the entire population and include people in group plans.)

But the state-based high-risk pools that existed before the Affordable Care Act covered only a tiny fraction of that population. According to Kaiser, the 35 states that operated high risk pools at their peak enrolled an average of 2 percent of the states’ non-group market participants in 2011. The cost of funding treatment for individuals with pre-existing conditions was a major constraint on the pools, experts say.

“The problem with it is it’s very inefficient and it’s hugely expensive,” said Sabrina Corlette, a research professor at the Center on Health Insurance Reforms at Georgetown University’s Health Policy Institute.

In order to rein in spending, many states imposed various restrictions on their programs. All of them charged higher premiums, usually 150-200 percent higher, than the standard market rate, with only 15 states subsidizing low-income consumers, according to a Kaiser report. The pools in 33 states imposed a lifetime cap, usually $1 million or $2 million, on what they’d cover, and 13 states also imposed annual caps on spending. High deductibles were also typical, and “nearly all” of the states’ programs, according to Kaiser, imposed a waiting period usually of 6-12 months where new enrollees could not get coverage for their pre-existing conditions in order to make “coverage less attractive for people who needed coverage specifically for their pre-existing conditions.”

(It’s worth noting that if the ACA was fully repealed, it would clear the way for a return of waiting periods or exclusions for those with pre-existing conditions on group plans as well.)

“They’re not affordable and they’re not very comprehensive in the way marketplace coverage is,” said Jean P. Hall, the director of the Institute for Health and Disability Policy Studies at the University of Kansas who has authored a number of studies on high-risk pools.

“Ultimately [the cost] comes out of the pocket of the individual who is covered by it,” she said.

That’s not to say that high-risk pools aren’t entirely unworkable, nor that some people didn’t greatly benefit from having them as an option before the Affordable Care Act. Ryan, while on CNN, pointed to the high-risk pool programs in Wisconsin and Utah, and indeed Wisconsin’s was larger than the norm (covering 6.8 percent of those in the non-group market) though still well below the estimated percentage of consumers who suffer from the pre-existing conditions insurers pre-ACA cited to prohibit coverage.

“There’s nothing wrong with it in theory, it’s just a second question that the resources available to these programs have to be established,” said Karen Pollitz, a senior fellow at the Kaiser Family Foundation,

The challenge is subsidizing them, as segregating the most costly individuals into their own pool means that the average cost is going to be, well, very costly. The average net loss per enrollee in states with high-risk pools in 2011 was $5,510.

A Commonwealth Fund study estimated in 2014 that it would cost the federal government $178.1 billion per year to fund a national high-risk pool program that would cover the Americans barred from insurance due to pre-existing conditions prior to the ACA. Health care experts at the right-leaning American Enterprise Institute pegged that number to be smaller — between $15 and $20 billion dollars annually– but for a program that would only cover 3 or 4 million people nationwide, and assumed a cost-model of the state-based programs that included the coverage restrictions.

The Obamacare replacement plan offered by Price, Trump’s pick for Health and Human Services secretary, carved out a mere $3 billion over a three-year period (or $1 billion per year) to fund high-risk pools for consumers who can’t get insurance due to pre-existing conditions. Ryan’s own proposal was only a little more generous, offering $25 billion over a ten-year period or $2.5 billion per year.

“That is like a drop in the proverbial bucket,” Blumberg said. “They’re kidding themselves if they believe that this is enough federal funding to make care adequate and affordable for such a high need population.”

Sheesh dummies, just rename the ACA the HFHS (Heritage Foundation Health System) and be done with it.

Your base won’t care and you’ll be good to go.

These are the same people that kept on telling us that they could cover everyone without spending a dime extra with vouchers and cost savings. Then Obama told them, okay, show me how we do that and I agree to do that. No takers on the show portion of the show and tell on health care.

The “high risk pools” myth is just the latest weaponry the GOP has chosen.

I think this is what disgusts and appalls me the most, the utter hypocrisy of the GOP. The entire ACA was nothing more, and nothing less, than an implementation of the GOP backed Heritage Foundation plan for a market based plan. But the fact that the Democratic party and Obama were the ones to implement it meant they disowned their own plan. You can actually find the original plan online if you ask Google nicely, I assume it is still out there, it was a couple years ago when I looked for it.

This is a perfect example of how our nation has become a post-truth society. The astounding and willful, militant ignorance of the American people is, in this case literally, going to be the death of them.

Heck, just call it DonaldCare.

DonaldDoNotCare might be more appropriate .