Just how sweeping was a last month’s federal appeals court decision declaring three one-year-old Obama recess appointments unconstitutional?

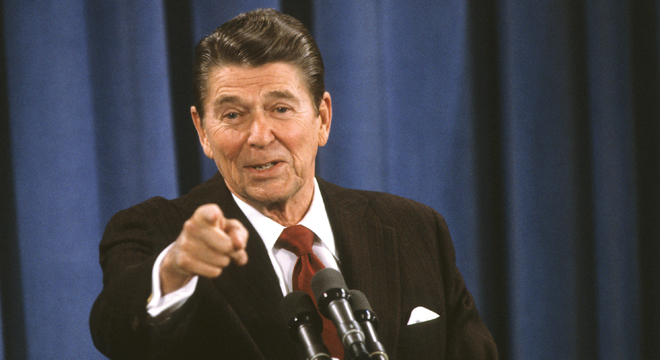

The Congressional Research Service turned back the clock (PDF) to the beginning of Ronald Reagan’s first term and dug up all the recess appointments they could find in the ensuing 32 years. Hundreds of recess appointments — by Presidents Reagan, H.W. Bush, Clinton, W. Bush, and Obama — would have been unlawful exercises of the recess appointment power had the new appeals court decision been in effect at the time, the CRS found in a memo dated Monday and released by Democrats on the House Education and the Workforce Committee, who requested the research.

The decision in January by the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals in Noel Canning v. NLRB was focused on the three recess appointments that President Obama made to the National Labor Relations Board in January 2012. The court held that none of the three board members was properly appointed, which voided the board’s decision in the case under review by the court. The ruling has thrown a year’s worth of NLRB decisions into question. It has also by extension cast doubt on the actions of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, which has been headed up by a recess appointee, Richard Cordray, whose appointment also did not satisfy the court’s standards.

But the scope of the appeal court decision was far broader than the particular circumstances of the NLRB appointments. The three-judge panel, each nominated by Republican presidents, re-examined the origins of the constitutional recess appointment power and concluded that the president has the power to make recess appointments only in one narrow circumstance: when the Senate is in recess between sessions of Congress and only if the vacancy arose during that recess.

The Congressional Research Service found a total of 329 intrasession recess appointments — appointments that occurred when the Senate adjourned in the middle of a session — since 1981. By the terms of Noel Canning v. NLRB, all of those appointments would have been invalid.

There were another 323 so-called intersession recess appointments — appointments that occurred between Senate sessions — but the CRS was unable to determine how many of those would also have run afoul of the circuit court’s opinion because it lacked sufficient data to determine whether those vacancies arose during the same recess. “Obtaining the precise dates on which each vacancy began can be difficult; therefore, at this time, CRS is unable to determine which of the intersession recess appointments listed in this memorandum would have been precluded under the court’s ruling,” according to the memo.

“Preliminary research suggests, however, that many of the intersession recess appointments listed in this memorandum might have been precluded, had Noel Canning been decided prior to January 20, 1981,” the CRS concludes.

The CRS does note that “almost all” of the now-questionable recess appointments have since ended and that the legally binding effect of Noel Canning v. NLRB decision was limited. “It should be noted that most of the recess appointments discussed in this memorandum are unaffected by the Noel Canning decision, which was limited in its scope to President Barack Obama’s January 2012 recess appointments to the National Labor Relations Board,” CRS said in the memo.

The case is expected to be ultimately decided by the Supreme Court.

Correction: Due to an editing error, the original version of this post incorrectly identified the head of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. His name is Richard Cordray. We regret the error.