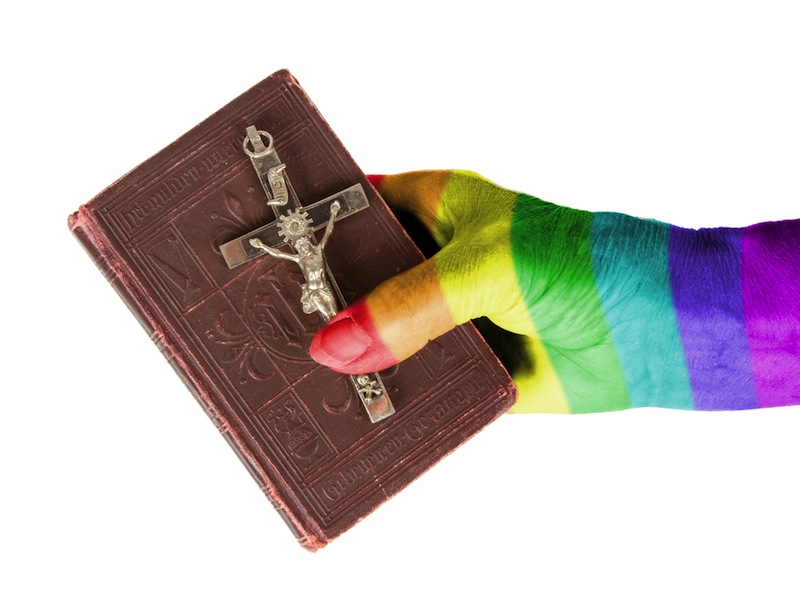

To many, the words “Gay Christian” are, at best, in tension with each other. For others, particularly those on the political right, those two words are mutually exclusive: being gay or supporting LGBT rights is utterly inconsistent with being Christian. But, as the recent viral video of outgoing Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd demonstrates, it is quite possible for Christians to embrace same-sex marriage and welcome gays and lesbians into their congregations. Pope Francis himself said this month that gays and lesbians “must be accepted with respect, compassion, and sensitivity.” Many gays and lesbians themselves are Christians. Yet somehow, in American political discourse, a group of religious politicians have managed to co-opt the term “Christian” and to use “Christian values” as a euphemism for policies that deny gays and lesbians their civil rights.

To suggest that one cannot be a member of the gay and lesbian community, or support their inclusion and legal rights, and be Christian is simply false. A number of Christian churches have expressed their support for inclusion and even the right for same-sex couples to be married, not only in the eyes of the state but also within their own religious congregations. The Episcopal church, the Presbyterian Church (USA), and United Church in Christ all permit the blessing of same-sex unions. A recent study by the Pew Research Center found that over half of Roman Catholics and white mainline Protestants support marriage equality. These persons of faith do not think of their support for gay rights as excluding them from the status of “Christian.”

Part of the perception problem is the use of “Christian” as some monolithic, uniform viewpoint. According to the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life, there are nearly 247 million practicing Christians in America; diversity of opinion is inevitable. Imagining that all Christians feel the same way about gays and lesbians also risks alienating gays and lesbians who are themselves persons of faith. For many, the process of accepting their sexual orientation is a complex, confusing process through which someone must risk family and friends to be true to themselves.

Often, and sadly, part if that confusion arises from religious viewpoints that treat gays and lesbians as, pursuant to the Catechism of the Roman Catholic Church, “intrinsically disordered” and morally inferior. To find full realization of your identity through any form of sexual expression is to render one a sinner destined for hell. For someone seeking the peace and love of God in a community that holds these religious views, theirs is a hopeless position: a life of sexual isolation or spiritual condemnation. The Pope himself noted that he received letters from lesbians and gays who felt “socially wounded” by the Roman Catholic Church. Even persons of perceived privilege can be impacted by the religious pressures. As professional soccer player Robbie Rogers noted, “Try convincing yourself that your creator has the most wonderful purpose for you even though you were taught differently.” My own campus at Emory University is reeling from the award to an alumnus of the theology school who actively worked to exclude LGBT persons from his church. It is not surprising, then, that many gays and lesbians ultimately leave their spiritual communities altogether and seek acceptance elsewhere. And such exclusion can be harmful to one’s sense of self.

For some, an important factor in their decision to come out may be their own spiritual identity. What drove me to finally wrestle with my sexual orientation had little to do with physical attraction. Instead, it was the complete frustration that my prayers to be straight would go unanswered, as if God was not listening and or simply did not care. The frustration and anger would mount until I simply began to doubt whether God existed. Yet, invariably, I would turn back to prayer. And through that effort, it came to me that perhaps my answer lay not in conversion but instead in acceptance of myself as God made me. Through that epiphany, I discovered not only a healthier sense of myself but also a more powerful and enriched faith.

Other gay Christians have shared similar stories. Rod Snyder, recent president of the Young Democrats of America, came out in August, noting that “Growing up in a conservative Christian family in rural West Virginia, my own journey to a place of self-acceptance has been a long and difficult one.” Nevertheless, he concludes that “it’s important to note that I didn’t shed my faith when I embraced my sexuality…. While there should always be room for theological disagreements, this debate is too often grounded in deep misunderstanding, only perpetuated by a culture of shame and silence.”

Of course, there are some Christian denominations that view gays and lesbians as immoral. Others try to walk the line of condemning sexual conduct between people of the same sex, but loving the people, “love the sinner, hate the sin,” as they say. But, under either approach, the relationships of gays and lesbians are viewed as utterly different and lesser than heterosexual ones.

Those who hold such values are free to practice their faith as they wish. But they should not be able to use the power of the state to inflict their particular religious viewpoints on those who disagree. In other areas of law and public policy, we have ensured that religious differences are protected and left to the discretion of the individual faiths. Divorce is viewed as sinful and inappropriate in a variety of Christian faiths. Nevertheless, our society has de-criminalized divorce and now permits the state to end the marriage, even if the marriage survives within the particular religion. For example, Catholics must seek dissolution of their marriages, which is separate and distinct from a divorce they may receive from the state. In the same fashion, those religious denominations who are opposed to same-sex marriages will not, and should not, be forced to perform or endorse same-sex relationships.

Our laws accommodate such variation in religious viewpoints. The First Amendment of the Constitution must allow us Americans not only to practice our religion freely but also to be free of the imposition of other religious viewpoints through government authorization. Similarly, denial of same-sex marriage denies the opportunity for those gay and lesbian Christians, and those who support their marriages, from being offered the full legal rights of marriage.

The religious right does not have a monopoly on what it means to be a Christian. Part of the beauty of being a Christian is learning of the rich diversity of views and interpretations of the Bible and other sacred texts. Christians who are gay, lesbian, or straight allies need to reclaim their Christianity. They need to speak out and identify themselves as Christian, with equal force of those opposed to gay and lesbian rights.

Such visibility has grown in recent years. At the two marriage equality cases at the Supreme Court last term, a number of groups filed briefs in support of marriage equality from a Christian perspective. Religious groups marching in the Chicago Gay Pride Parade in 2013 stretched across two city blocks. Even the Pope stated, “If someone is gay and he searches for the Lord and has good will, who am I to judge?” This month he noted that the church should not “interfere spiritually in the life of a person.” Such visible and vocal displays of support for the rights of gays and lesbians is crucial to reclaiming the identity of Christianity in the public arena. It is time to recognize that “gay Christian” is not an oxymoron; instead it is a statement of truth for a large part of the Christian community.

Tim Holbrook is Associate Dean of Faculty and Professor of Law at Emory University School of Law. He was co-counsel for two NFL players on a Supreme Court brief in one of the same-sex marriage cases last term. He is a an Op Ed Project Public Voices Fellow.