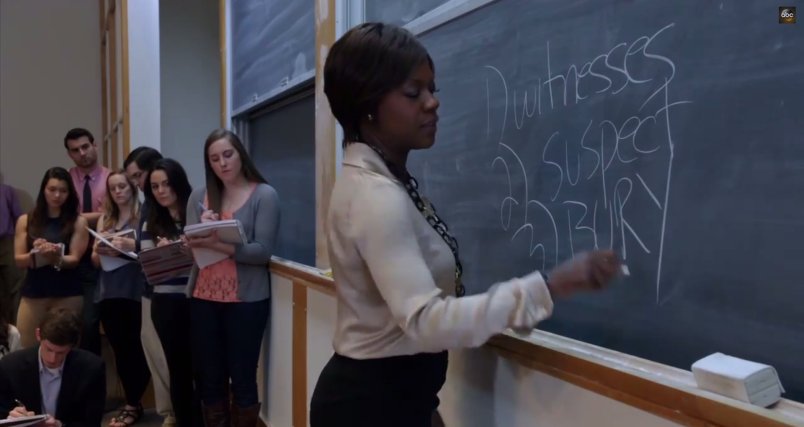

Last month, Nellie Andreeva wrote a piece for Deadline on race in contemporary television that set the Internet ablaze. In the article, Andreeva ponders whether the current array of multiracial castings in popular shows (How to Get Away with Murder, Scandal, Jane the Virgin, The Mindy Project) or, in some cases, shows that deal specifically with the experiences of people from a particular community of color (Black-ish, Fresh Off the Boat, Empire) have gone “too far.” Andreeva asks her audience to consider, though she does not quite state it outright, the cost to white people of seeing people of color on television.

Andreeva does not explore what people of color think about the current TV landscape or the significance of seeing themselves reflected in mainstream media. She does not examine existing or potential pathways for more people of color to enter the writers’ room or sit on the director’s chair. Instead, she reinforces the idea that whatever loss white people might experience trumps all.

While it’s easy to cast off discussions of pop culture as trivial or inane, Andreeva’s article draws on and reinforces a logic with deep, pervasive implications. It is the axiom according to which white folks organize our histories, our lives, our relationships: In a world based on whiteness, there is only room for one winner — and it had better be us.

Take, for instance, the creeping anxiety among white folks in the U.S. about our impending “minority” status. The most recent projections from the Census Bureau name 2044 as the point when people of color will collectively outnumber white people in this country. This demographic reality has fostered a deep sense of paranoia about a pervasive existential threat, not just to white people but also to white institutions, values, and culture. White folks are, irrationally, afraid of being wiped out.

The irony of this fear shouldn’t be lost on us — white people simply wouldn’t exist as we do today, embedded within and sitting atop a racial hierarchy, if it weren’t for systematic violence against Native people and African slaves in the early years of colonialism. We have learned, over the course of generations, that the path to power runs through the graveyard.

And so, the zero-sum game of racial politics is a throughline to the epidemic of state-sanctioned violence in this country. It lives and breathes the idea that white people are made safer by a police state that makes people of color less safe. The brutal and relentless crackdown on undocumented immigrants of color and the xenophobic rhetoric that supports it are evidence of this mentality, but more importantly, of its consequences — families unhinged, children denied asylum from violence, persistent poverty.

It is not, of course, just immigrants whose success, whose very existence, is viewed as threatening to white people’s stability and security. On April 4, in North Charleston, South Carolina, a white police officer named Michael Slager shot Walter Scott, an unarmed black man, eight times as he fled for his life. Scott had committed no crime — Slager erroneously pulled him over for a busted tail light, even though South Carolina only requires drivers to have one working tail light. Feidin Santana’s video revealed an ugly, naked truth about police violence that black people don’t need a tape to prove: that white cops seem to relish their ability to inflict lethal violence on black bodies. And yet, without Santana’s evidence, Slager would likely still be a cop on active duty.

Despite the unequivocal proof of Slager’s brutality, mainstream media can’t seem to shake off the familiar narrative it rehashes each time a black person is murdered by cops. News outlets, whose response to 12-year-old Tamir Rice’s death at the hands of two white police officers in Cleveland was to dig up dirt on Rice’s father, is well-primed to make any black victim of violence a criminal or criminal-by-association. Just look at Mike Brown,Trayvon Martin, Shantel Davis. These stories deny that black victims of police violence — and all black people — matter simply because they are people. They should have had, and in death should still have, nothing to prove.

When white cops are free to gun down black children, black women, black men, with impunity and the media engages a sustained smear campaign against the victims, the message is that the loss of black life should be understood as a net gain for white people. The various Michael Slager support funds that have popped up on crowdfunding sites reveal that there are plenty of white folks willing to reward black death with money and emotional support.

On the flip side, white people routinely fail to empathize with black people and people of color in general about their pain and grief. But is that particularly surprising, when we’ve been taught our whole lives that our success depends on other people’s failure?

Which brings us back to Andreeva’s article and the subtle violence it perpetuates. When we ask whether we’ve gone “too far” in creating spaces for people of color to explore and articulate nuanced, intricate life experiences, we are reinforcing the idea that only one narrative — that people of color represent a threat to white people — can or should endure. Left unchecked, this belief is the bedrock for the justification of everything from forced deportations to police killings. We cannot do the hard work of reshaping both the limits of our own empathy and the structures of our institutions if we continue to buy into the logic of the zero-sum game.

The sustained assault on people of color in the U.S. demands, at the very least, the dignity of better questions. Rather than wonder what white people might lose if people of color win, we should start by asking why we continue to tolerate, even condone, a world where the cost of protecting whiteness is measured in real, valuable lives lost.

Adrien Schless-Meier is a writer and editor currently working in philanthropy in Washington, D.C. She is the former deputy managing editor of Civil Eats, and writes about her varied interests on her own blog. A version of this piece originally appeared on Medium.

Speaking as a 56 year old white male, we are incredible whiners if all we do all day is worry about whether there are enough TV roles for white people and become envious of all the great roles for “other” people.

The author is a pearl clutching blogger with a weak resume whining about her white status as if she’s speaking for the white race. And she says the dumbest things:

“the message is that the loss of black life should be understood as a net gain for white people.”

Really?

I just find it sad and pathetic when white folks (usually in other websites) start complaining about how they’re so tired of hearing about race.

I guess I would be tired hearing about race too if others kept pointing out to me that folks who look like me keep treating others as beneath them on an every day basis, both consciously and unconsciously, have done so for centuries, and in many ways still do. And that I directly and indirectly benefit greatly from that… Or at least I would be if I had no empathy as a human being, capacity for introspection, or self awareness. SMH.

I don’t think you understand the phrase “pearl clutching”. It doesn’t mean “gets upset by senseless killing.” The phrase you are looking for is “minimally human”. That’s a goal you might aim for.

“Andreeva asks her audience to consider, though she does not quite state it outright, the cost to white people of seeing people of color on television.”

I’ve read the article, and in my opinion it does no such thing. It simply asks if the self-imposed quotas for ethnic actors have taken things too far. Considering the article appeared on Deadline, a web site devoted to Hollywood’s ‘inside baseball’ it seems like a legitimate topic to cover.

The real controversy appears to have been caused by the incredibly offensive, idiotic click-bait headline that first appeared with the article and which referred to a “plague of ethnic actors” and which Deadline now admits did not reflect the content of the article.

Edit: and for what it’s worth, I don’t think the pendulum has swung too far (easy for me to say since I don’t work in Hollywood). I don’t watch a whole lot of TV, but I watch enough to know that TV is waaaay more interesting these days than it was, say, 20 years ago, and that is due in part to how much more diverse it is.