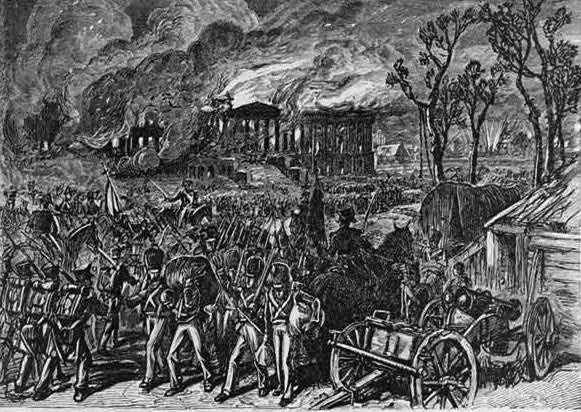

The White House burned. So did the U.S. Capitol, and most of the public buildings in Washington, D.C. Invading British troops burned the city in this most humiliating episode in American history 200 years ago today. Some are tempted to call the War of 1812 “the forgotten war,” but that is absurd. Out of it came the national anthem, a daring act of bravery to save the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, and the most lopsided defeat of the British military in all of their conflicts.

The British struck at the nation’s capital to weaken the morale of their enemy, and as payback for American excesses in York — what we now call Toronto — where they had pillaged and burned public and private buildings. Admiral George Cockburn, the driving force behind the attack on Washington, had justified the fall of a capital as “always so great a blow to the government of a country.”

No one expected that the British infantry would march 50 miles inland to storm the capital. It was too far off, and they would have to slog through woods and dense thickets and brush to achieve their goal. No one even knew their target. There was speculation that they might swing toward Baltimore, Annapolis, or even sites further south.

The man most responsible for the catastrophe was none other than the Secretary of War, John Armstrong, of whom it was said, “Nature and habits forbid him to speak well of any man.” When a frantic head of the capital’s militia went to see him, the officious and stubborn secretary of war belittled the threat to the capital.

“They would not come with such a fleet without meaning to strike somewhere. But they certainly will not come here!” he said. “What the devil will they do here? Baltimore is the place.” Later he would become the most reviled man in the country and resigned from office.

As the British wilted in the hottest month of the year, pandemonium overtook Washington, where nine-tenths of the city’s population of 8,000 escaped to the woods, some going as far as neighboring states.

At the state department, treasury official Stephen Pleasonton gently put the originals of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution into linen bags, and fended off a reprimand from Armstrong by saying he thought it prudent to try to protect the documents of the revolutionary government. He carried the priceless trove to Leesburg, Virginia, where he locked them in an empty house.

The president’s wife, Dolley Madison, risked death or captivity by refusing to flee the White House to join her husband in Virginia until she had seen the full-length portrait of George Washington by Gilbert Stuart taken down from the dining room. The painting was then escorted to safety in the countryside by her friends, Jacob Barker and Robert dePeyster.

At the House of Representatives, a colleague managed to rescue some official papers in an impounded cart with four oxen, but the remainder burned, as did all 3,000 books of the Library of Congress. A clerk saw signs of “doubt, confusion, and dismay” in Washington before he and two assistants loaded an impounded wagon with the senate’s only copy of its quarter century of executive history and other writings, then escaped, with the retrieved records ending up in Brookeville, Maryland, a Quaker village, some 25 miles north of Washington.

The British troops, after defeating a numerically superior force of mostly green militiamen at Bladensburg, six miles northeast of Washington, marched up to Capitol Hill, where they saw the Senate on the north side and the House on the South, linked by a wooden walkway. They brushed past fluted columns, raced up grand staircases, under archways into vestibules with vaulted ceilings. The architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe had created a building to rival its weathered counterparts on the old continent of Europe. It was a symbol of the hopes and aspirations of the young republic. The British used furniture and wood from doors and window frames to set fires, overriding objections from junior officers not to destroy works of art.

Only 100 soldiers and sailors marched down deserted Pennsylvania Avenue to burn the executive mansion. As they entered the White House, Admiral Cockburn hauled in a young American bookseller: Roger Chew Weightman, who would later become mayor of Washington. He would be humiliated as the unwilling representative of America and Cockburn taunted him with mischievous relish, while his compatriots drank pilfered wine and looted, even as others built a bonfire in the elegant oval room. Only roofless walls remained. A charred archway under the present front door is the most visible sign of the British fires from 1814. That night the British also burned the Treasury, and the following morning the State and War Departments, and the rope walks, which sent plumes of black smoke over the capital.

The next day they burned what had not been preemptively destroyed by the Americans at the navy yard. The British also ransacked the press and offices of the National Intelligencer, a newspaper considered a government mouthpiece. A violent storm on Thursday afternoon struck the city with ferocious winds, though eyewitnesses saw flames still burning days afterward. The vandals stayed only 26 hours, needlessly concerned that they would be attacked while returning to their ships.

Just three weeks later, humiliation turned to glory. The same British forces bombarded Fort McHenry with between 1500 and 1800 shells, but no one ran from his post, even though there was no cover. The noted Georgetown lawyer, Francis Scott Key, was an eyewitness, having secured the president’s permission to board the British ships to gain the release of a captive friend, but he himself became a hostage after being promised his freedom once Baltimore was taken.

At sunset he had seen a giant Star-Spangled Banner flying over the fort as an act of defiance.

What so proudly we hailed at the twilight’s last gleaming.

Unaware of the result, Key waited until dawn, when he clearly made out the Stars & Stripes.

O say can you see by the dawn’s early light.

Never before had he looked with such reverence upon the symbol of his country. On the back of a letter, he wrote down anything that raced through his mind in the intensity of the moment. When the British skulked away three days later, unable to subdue the fort, Key’s poem became the lyrics for a national anthem, set to the tune of an old English drinking song.

Finally, A Treaty of Peace and Amity, signed in Belgium on Christmas Eve, ended the two-and-a-half year costly war between two exhausted nations, but before it could reach America the armies faced each other at New Orleans. Andrew Jackson had galvanized his force of frontiersmen, ruffians, pirates, and militiamen, but the well-trained British were impatient. They charged over a flat field of sugar cane stubble without any cover and were picked off by skilled sharpshooters.

When it was over there were more than 2,000 British casualties. There were only six American dead, and seven wounded. America had thrashed the finest army in the world.

The second War of Independence was over.

Anthony S. Pitch is the author of The Burning of Washington: The British Invasion of 1814, a selection of the History Book Club, with movie rights optioned by National Geographic, and according to the White House and the Associated Press, read by President Clinton.

—

Image credit: Library of Congress

And the US objective in starting the war? To annex Canada while the British were busy fighting Napoleon in Europe.

Of course like most parts of the US origin fable, that explanation is not acceptable so it is pretended that the war was over impressing seamen. The school history books don’t mention that the principal concern of the Whig faction behind the Boston tea party was that Britain might end the very profitable Boston slave trade (it was the central hub).

Oh and that civil war thing? It was all about slavery from start to finish.

There is a similar effect in British school history books. The history of the 100 years war with France has victory after victory. Then you turn the page and we are suddenly down to just having Calais and nothing else.

I expect this to be on the Fox channel soon, denouncing Obama.

Wow! He has a real talent for rewriting history! I actually live in the actual town (Newark, now called Niagara-on-the-Lake), and not York (now called Toronto) which was burned to the ground before the Yanks left in defeat. The only buildings remaining were stone structures.

The War of 1812 is celebrating it’s Bicentennial. The River Raisin National Battlefield Park is the only battlefield dedicated to the War of 1812. Check it out!

http://www.nps.gov/rira/index.htm

That wasn’t the objective in starting the war. It became a half-hearted objective later on.

The war started because of three things:

Annexing Canada only became part of the plan after the invasion began and was going well. Politicians as they usually do think war is easier than it is and thought the invasion would be easier than it was. President Madison wasn’t among these and never had any intention of annexing Canada. If he was so gung ho to take advantage of the Napoleonic Wars then why did he have to have a naval battle off the coast of North Carolina to get him to declare war after YEARS of cries for war from warmongers in Congress? He was near the end of his first term as President when the war began, and the origins of the war started in the latter part of Jefferson’s presidency. He didn’t take advantage of Napoleon’s routing of Britain. Yes, there was a U.S. election in the middle of the War of 1812. Madison won his second term.

If the war was truly about the annexation of Canada then why did the war begin with a naval battle off the coast of North Carolina? What was the British ship even doing there? That caused the declaration of war (after a new Congress convened and Liverpool blew him off essentially saying he had bigger fish to fry). The war began officially in the “West” (Ohio on up to Michigan) and not Canada. It continued into Canada, of course, when fighting Tecumseh. Annexation talk didn’t begin until the official invasion later.

To be fair to the British the country was in disarray after the assassination of Spencer Percival. They didn’t have a clue as to what was going on here until after the war began. Parliament had no clue why we cut off trade with them. Communications then weren’t instantaneous like it is now. A ship had to travel across the Atlantic with messages. The war began because Parliament couldn’t keep a hold of its navy, and it ended with a massacre of the British forces long after the treaty was signed because no one told either side the war was over.

The war was stupid and pointless, but it’s the second war of independence per se because after the war we were finally recognized by Great Britain, and trade with them actually increased.