In an era when our wars seem too often fought far away, literally and figuratively, from the majority of Americans’ lives, Memorial Day serves a vital purpose: providing cultural space for those who have lost loved ones in war. It offers us images and commemorations of fallen soldiers—a communal chance to remember and honor the lost.

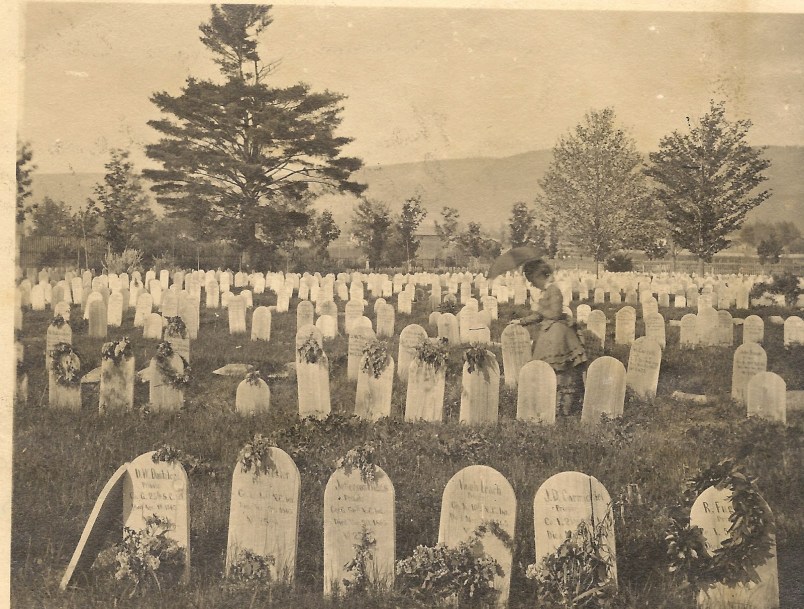

Yet Memorial Day’s original meanings and narratives are significantly different from, and would add a great deal of complexity and power to, how we see them nowadays. The holiday was first known as Decoration Day, and (per thorough histories by scholars like David Blight) was originated in 1865 by a group of freed slaves in Charleston, South Carolina. The slaves visited a cemetery for Union soldiers on May 1st of that year and decorated their graves, a quiet but very sincere tribute to what those soldiers have given and what it had meant to the lives of these freedmen and women.

The holiday quickly spread to many other communities of former slaves, and then to the North and nation as a whole. Yet just as quickly, national Decoration Day celebrations began to focus on less potentially divisive perspectives of former soldiers, not to mention ones far less focused on slavery. Indeed, by the 1870s the commemorations featured veterans from both sides, as illustrated by prominent former Confederate Roger Pryor’s 1877 Decoration Day address in New York.

Yet despite this telling national shift, former slaves continued to honor the holiday in their own way, as evidenced by a powerful scene from Constance Fenimore Woolson’s local color short story, “Rodman the Keeper” (1880). Woolson’s protagonist, himself a Union veteran living in the South, observes a group of ex-slaves leaving their decorations on the graves of the Union dead at the cemetery where he works as a caretaker.

On one hand, these ex-slave memorials to fallen soldiers offer a parallel to the family memories that now dominate Memorial Day, and serve as a beautiful reminder that the American family extends to blood relations of very different and equally genuine kinds. On the other hand, the ex-slave memorials represent far more complex and communally significant American stories and perspectives than any individual familial memory. These Decoration Day commemorative acts offered a vital acknowledgment of both some of our darkest histories and the ways in which we had overcome them at great but necessary cost.

I’m not trying to suggest that current celebrations of Memorial Day are anything other than genuine and powerful. I’ve heard the eloquent words of my grandfather, Art Railton, about what experiences with his fellow soldiers meant to him; he even commandeered an abandoned bunker and hand-wrote a history of his Company after the war. But as with so many of our national histories, what we’ve forgotten is just as genuine and powerful, and often a lot more telling about who we’ve been and thus who and where we are. The more we can remember those histories, too, the more complex and meaningful our holidays, our celebrations, our memories and our futures will be.

Ben Railton is an Associate Professor of English at Fitchburg State University and a member of the Scholars Strategy Network.

Amen.

We spent 4 years fighting the Civil War, and the next 150 years trying to distort the history of it. Thanks, Mr. Railton for your effort here to inform us of our past.

There are towns across the country that claim to have been the place where Memorial Day was invented.

And all those claims are true, in a sense. In the late spring of 1865, I suspect people in many places spontaneously joined together to remember their dead and to rejoice that the war had finally ended. It would have been a natural thing to do. So I don’t pay much attention to any one place’s claims to fame at the birthplace of what became a national event.

In the middle of the last century, when I was young, many people still called the day “Decoration Day.” Everybody, or so it seemed, went to the cemeteries where their loved ones were buried (all loved ones, not just war dead) to tidy up the graves and leave bouquets of flowers. Because the day fell anywhere during the week, people were off work or out of school for the day only, so commemoration was the rule.

It’s a shame we lost that when we moved the day to a Monday and set up everything for partying and shopping. We ought to be willing to give just one day of the year to remember all our ancestors, and to remember the sacrifices of those who served.

“I’m not trying to suggest that current celebrations of Memorial Day are anything other than genuine and powerful.”

Nor will I, but I will add that they are also jingoistic and perpetuate the illusion that might makes right.

I would only hope that on Memorial Day we also remember all the innocent lives we’ve taken as a result of wholly unnecessary conflict sold to the American people with a mountain of lies. And remember all those innocent Americans killed from the blowback of our murderous foreign policy conducted not on our behalf, but on behalf of the plutocrats whose future generations will inherit their wealth and never serve anyone but themselves. And remember too that sending our own precious patriots to risk life and limb and psyche for no good reason is not to be tolerated, and that honoring their sacrifice is poor recompense for exacting that sacrifice without justification.

But I’m afraid that unless war criminals in high places are actually prosecuted, these aspects of genuine and powerful sentiment will never be respected.

Obama long ago informed us we need to look forward, not backward, so learning anything from history and providing deterrents for future war crimes are, as Nancy Pelosi put it, “off the table.”

OK, America, back to the barbecue and the beer.

Thanks for the comments, all. While I agree that the holiday sprung up out of that widespread communal sentiment, the specifics of Decoration Day are tied closely to ex-slaves’ commemorations, and whether we call them the first celebrations or just a key part of the origins, we need to better remember them and what they offer us.

Thanks,

Ben