Today, the Tea Party has a chance to for a major victory. In Mississippi, Republican voters are going to the polls today to decide whether to re-nominate six-term Senator Thad Cochran or to replace him with Tea Party favorite Chris McDaniel. Given that Tea Partiers have already claimed at least one huge primary victory this year by defeating House Majority Leader Eric Cantor, it is time to look at a larger question: are primary elections promoting extremism?

Analysts and media commentators argue that primaries discourage moderation and bipartisanship. Incumbent members of Congress – Republicans, and to a lesser degree, Democrats – are said to be dissuaded from searching for bipartisan solutions to national problems because they fear they could be outflanked by more extreme challengers in party primaries. Because many Americans do not vote in primaries, the voters who turn out are allegedly more ideologically extreme. Fearing challengers who may attract such voters, the story goes, incumbent officeholders shy away from moderate positions and legislative compromises. In the general elections, consequently, majorities of relatively moderate voters are forced to choose between candidates who pose ideologically extreme choices.

Although there certainly have been several high-profile primary challenges in recent years, my research suggests that this received wisdom is largely incorrect. Primary challenges have not become more common, and if incumbents fear primaries more today, their qualms are based more on what they hear about primaries than on what actually takes place in these elections.

Over the past four decades, it turns out that there has not been any increase in either the sheer number of challenges or the proportion of successful challenges.

In elections to the House of Representatives, primary challenges were more common in the 1970s – when they averaged 49 per year – than over the most recent decade – when they have averaged 38 per year. The 2010 election year did see an increase in challenges.

In the Senate, the number of challenges fluctuates but there is no evidence of a trend.

Defeats of incumbents are rare, and it is very rare for a successful challenger to go on to win the general election. In years with no redistricting, no more than three or four Congressional incumbents are likely to lose their primaries. For the Senate, 2002 was the last election in which a successful primary challenger went on to win the seat.

Upticks in primary challenges do happen from time to time – especially within a party that experiences a surge of election victories in a given year.

- In 1974, overall Democratic general election gains were accompanied by a large number of primary challenges to incumbents, often from anti-war candidates or other liberals.

- In 1994, GOP general election gains followed many primary challenges from candidates accusing Republican incumbents of being too willing to work with President Bill Clinton.

- In 2006 and 2008, Democrats gained seats in the House after many contested primaries where incumbents were criticized for not doing more to oppose the Iraq War or the priorities of the George W. Bush administration. Recent upticks in Republican primary challenges since 2010 fit this same pattern.

Primary challenges are not all the same. Recently, attention has focused on ideological challenges – for example, when incumbent Republicans are challenged from the right. But primary contests are not usually about ideology. Challengers usually target incumbent who are accused of ethical lapses or otherwise embroiled in political or personal scandals, or they challenge incumbents showing signs of infirmity or incompetence.

Why is it, then, that primary challenges have commanded greater attention in recent years? Although most bids are unsuccessful, each of the past five election cycles has featured a few high-profile challengers. These challengers are different from average primary challengers in three ways.

First, high-profile challengers framed their races as referenda on their party’s ideological purity. Seeking to present themselves as unorthodox candidates or “anti-politicians,” they have adopted extreme stands and run advertisements designed to set them apart from “conventional” politicians.

Second, high-profile challengers raised substantial amounts of money nationwide – either from small contributors or from major donors outside of their states or districts.

Third, high-profile challengers garnered support from ideological, multi-issue interest groups (such as MoveOn.org or the Club for Growth) that have long sought to push their parties away from the center. For such groups, media attention is more important than whether their candidate actually wins.

In recent years, high-profile ideological challenges have been more common in the Republican Party because Democratic multi-issue groups have concentrated on protecting vulnerable incumbents. Ideological challenges in each party also tend to take on a different focus. On the left, Democratic challengers tend to criticize the relatively moderate voting records of the incumbents they face, whereas GOP challengers from the right criticize incumbents’ demeanor – for example, willingness to compromise – more than their typically conservative voting records.

Given a careful review of the last four decades, there is no reason to conclude that primary elections are driving ideological polarization or preventing compromise in Congress. Some incumbents may be reacting fearfully to a few high-profile contests, but primary challenges are not, by themselves, the major cause of increased polarization in US politics. The causes of polarization lie elsewhere.

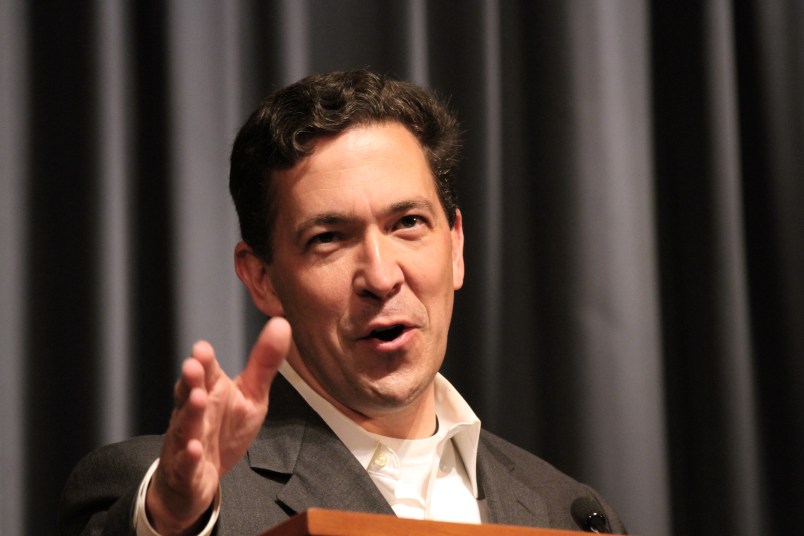

Robert G. Boatright is an Associate Professor of Poltical Science at Clark University and a member of the Scholars Strategy Network. He is working with the Campaign Finance Institute to monitor interest group spending in this year’s primary elections; for more details see here.

I blame right-wing media, which poison the minds of their highly susceptible consumers with propaganda and lies.

“The causes of polarization lie elsewhere.”

It’s the media.

I always say, vote longterm incumbents out. longterm incumbents with their greedy ivy league staff are responsible for the inequality that exist in our economy today. mcdaniels is probably the biggest jerk running, however get the incumbent out first and in two years a better candidate will run

" mcdaniels is probably the biggest jerk running, however get the incumbent out first and in two years a better candidate will run"

Of course the obvious flaw in this argument is that if McDaniels wins, he will almost certainly win the general and it will be six years not two before a better candidate can run. The real question is how much damage to Mississippi and to national politics will McDaniels do in those six years? Judging from his rhetoric and his past statements the answer is also obvious, plenty.

The great irony is that with the loss of the seat on the Senate Appropriations Committee, Mississippi property taxes and income taxes will have to either rise dramatically to cover the loss of federal funds or Mississippi will give new meaning to the phrase “Number 50 of 50”. All indications are that it will be a combination of both and racial politics in Mississippi are about to turn very ugly again.

It is a six year term.