On Presidents’ Day, officially known as Washington’s Birthday, we celebrate neither our presidents nor the father of our country. Lost amongst the car sales and piled snow, not to mention our political cynicism and distrust, is the presumed purpose of the holiday: to remember great leadership.

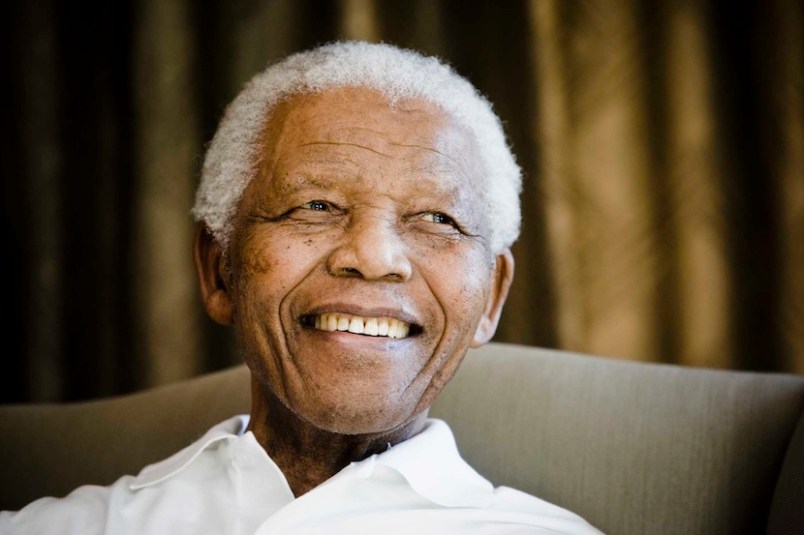

Thinking about what makes for outstanding public service is especially pertinent in 2014, both at home and abroad. While our own Washington has been dead for over two centuries, he remains a benchmark for leadership. Nelson Mandela, contemporary South Africa’s founder, statesman, and secular saint, is only recently buried.

Washington and Mandela stand as remarkably parallel figures. They deserve praise and commemoration for their character, devotion to nation, and skillful maneuvering in establishing peaceful democratic traditions and new constitutions–in climates inhospitable to both.

But citizens need to grapple with a more complex legacy of these political icons. We should recognize the limits of their examples, and the dilemmas they leave for us today.

Part of what makes Washington and Mandela stand out as leaders is that they were as popular in life, embroiled in the messiness of day to day rule, as they were in death, when our memories become softer, our judgments more forgiving. For citizens and scholars, the adulation of these figures by both contemporary and future generations makes retrieving and assessing their stories especially difficult.

Both men’s status owes something to their long and varied contributions to their people. They stoically led their countries through a variety of trials. Washington was commander of the Continental Army, presided over the Philadelphia Constitutional Convention, and, of course, served twice as president. At each phase, he was a stabilizing force for an emerging nation taking uncertain and hazardous steps.

For his part, Mandela led an opposition African National Congress (ANC) in the 1950s, co-founded the military wing of that organization a decade later, and spent years on the run before being arrested, tried for treason, and imprisoned on Robben Island for 27 years.

In 1994, with South Africa near collapse, he emerged from prison to negotiate a largely peaceful transition from apartheid. Like Washington, he morphed from revolutionary figure to civic force: helping create a new constitution and serving as president.

At great personal risk, both leaders faced off against a well-armed and well-financed opposition. In overcoming these adversaries and in presiding over the subsequent political makeover, Washington and Mandela became essentially mythological figures.

Their countries saw them as uniquely capable of overcoming festering domestic divisions and serving as the basis for new national narratives of patriotism and hope. Thomas Jefferson’s words about Washington reflect popular attitudes towards both: “never did nature and fortune combine more perfectly to make a man great.”

But what of their more specific political legacies? Washington and Mandela took on important problems of governance, such as confronting America’s Revolutionary War debt and investigating human rights violations through the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

But perhaps their most remembered and enduring contributions arise from their decisions to serve for limited periods. And here lie some of the inherent problems posed by their leadership as well.

Washington renounced power on several occasions, most famously in refusing to run for a third presidential term. Despite budding criticism of his administration, most scholars and contemporaries agree that Washington would have secured reelection. But Washington refused, in order to ease worries that the executive branch would become the seat of tyrannical rule. He also longed “to return to that domestic retirement” which he had “left with the greatest reluctance.”

Washington’s desire to quit public life fits with our widespread suspicion of those seeking power. Americans have a longstanding tradition of admiring leaders who seem deeply ambivalent about governance–those who refuse elected office or assume office by disparaging politics and other elected officials. But these figures make governance problematic, especially when they lack Washington’s seemingly quaint sense that service is one of the best conduits for public honor and esteem.

Despite his voluntary retirement, Washington did not obviously support presidential term limits. For Mandela, however, this element of his leadership was critical. As noted, he developed the South African Constitution of 1996 which restricts presidential service to two terms.

Further, in leaving office after only one term, Mandela regarded himself as a counter-example to the lamented African tradition of “presidents for life.” Indeed, he was sufficiently sensitive to this issue he quietly opposed his successor, Thabo Mbeki, from securing a third term as president of the ANC, following two terms as president of the nation.

As much as we praise Mandela’s efforts to counter autocratic rule, his behavior also came with a pointed political cost. Economic inequality, high crime rates, and an unchecked AIDS epidemic, continue to burden South Africa. Moreover, the absence of a legitimate political opposition means the ANC so dominates the nation’s landscape that observers fear it fosters corruption and protracted rule, threatening the very ideals of democratic transition supported by Mandela. His inimitable charisma, life story, and political skills may have provided just the right mix to address these vexing concerns.

Mandela’s wish, like Washington’s before him, to enjoy life away from the public eye, and to keep his legacy intact, contributed to his decision to retire. The concern is that in acting on these very understandable, very human motivations, Mandela may have deprived his country of the one leader who could take on its most important and intractable political challenges.

Robert Houle is an Associate Professor of History at Fairleigh Dickinson University (FDU) and author, most recently of Making African Christianity: Africans Reimagining Their Faith in Colonial South Africa. Bruce Peabody is a Professor of Political Science at FDU and the author of The Politics of Judicial Independence. He is currently writing a book on changing conceptions of American heroism.