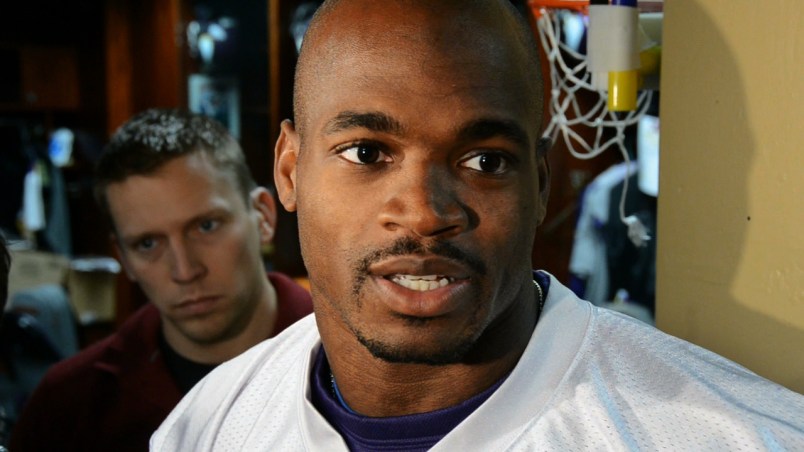

Don Lemon is back at it. After embracing the idea of how respectability politics could have saved Trayvon Martin’s life, Lemon has set his sights on the moral failings of unwed parents. In a piece published at Black America Web, the CNN anchor wrote about the tragic beating and ultimate death of the two-year-old son of NFL superstar Adrian Peterson at the hands of a man who was not the boy’s father:

“This Adrian Peterson secret love child beating death story has been really bothering me,” Lemon said. “Bothering me obviously because the boy was just two years old and was allegedly beaten to death by his mom’s boyfriend who was not the child’s father.

Bothering me also because the dead boy’s father is Minnesota Vikings star running back Adrian Peterson, an NFL MVP, who appears to be more MIA, than MVP.”

This time, Lemon has joined the growing public discourse (it so polite a word as discourse can be used) that wants to find some moral failing in Adrian Peterson to help us understand the tragedy of his murdered child.

This critique all hinges on the assumption that without such guidance we would all make the mistake of simply mourning a tragic crime when we should instead be finding someone to blame. The driving need to find a villain is a condition of the American psyche, perhaps even of the human psyche. But American culture seems particularly fond of turning messy human interactions into a clear morality tales with bad guys and good guys. Some people even come close to making these morality tales an art form. Don Lemon is not one of them.

Just a year ago, it would have been hard to imagine that CNN’s clean-cut milquetoast news anchor would become a voice of black conservatism, assuming that is what he is. I’m not so sure. I think it’s more to the point to say that Lemon has joined a long line of culture of poverty advocates who blame for pay.

Sociologists spend a lot of time trying to understand why poverty exists. One of the most popular ideas to emerge from this cloistered academic discourse is the idea that poor people are poor because they have a poor culture. The American penchant for morality tales really likes this notion. It justifies the inevitable consequence of capitalism that requires there always be poor people. Poor culture is the bad guy in the black hat and equal opportunity and good morals is the white hat on a horse. Culture-of-poverty folks like to talk about “personal responsibility” and “faith” and “values” as if they have cornered a limited market on these things. They rarely talk about how poor people believe mightily in personal responsibility, even when doing so ignores all the empirical evidence of their daily lives.

In his interviews with impoverished black men in urban Chicago, Alford Young reveals how cognitive dissonance looks on the ground. These men related tale after tale of employment discrimination, police profiling, underfunded schools, dangerous public spaces and spatial inequality. Yet, when asked if they think they are victims of a bad system, the men overwhelmingly shoulder all the blame for how their lives turned out.

Single parents tend to live the same kind of dissonance. Many accept the personal responsibility Don Lemon clumsily articulates as an innocuous alternative framework for understanding the death of Adrian Peterson’s two-year-old child. He isn’t “blaming anyone” but he just wants to bring to your attention that bad single parents are bad. Lemon’s hedge is dishonest in its attempt to be both a moral condemnation and rational framework. He does not want your consideration of violence and abuse to neglect to blame the culture of poverty that is embodied in unwed parents like Adrian Peterson. He wants to draw your attention to dirty culture without getting any of the mud on his finely tailored suit.

How did we get to this, Don Lemon? There’s always been money to be made for members of any group willing to be the public face of self-flagellation. That story is as old as caricatures of Uncle Toms. But to reduce this phenomenon to individual moral failings is to make the same mistake Lemon makes when he inserts personal responsibility into a private tragedy of a public figure. CNN, MSNBC and Fox News have been battling for top-dog in cable news ratings.

In 2012 CNN was feeling the heat when the network hired Jeff Zucker to right the rating’s ship. One of Zucker’s first moves was to push out the network’s resident race auteur, Soledad O’Brien. Sources at the time were cited as saying, “Soledad is talented at producing in-depth, serious pieces of journalism, and is a tough interviewer. That doesn’t seem to fit the direction the network is going.” That move cleared the way for Don Lemon’s star turn as black culture of poverty pundit.

What is the “direction the network” was going? So far it seems to be going for demographic spaces it thinks it can win. Melissa Harris Perry, Rachel Maddow and Chris Hayes on MSNBC have developed a cult following among diverse viewers. Harris Perry, in particular, leaves little space for which a progressive black voice without her academic and rhetorical chops can compete. That is not to say Lemon, the person and not the pundit, would have been inclined to be a progressive black voice. But it certainly adds some context as to the timing of his decision to sharpen his rhetoric and take aim at the personal moral failings of the black community.

Lemon is a news reader, not a reporter or even a producer. He has certainly not been on the trajectory to become a public intellectual. Until O’Brien left, he was not known for taking on topics like “the N-word: should we use it“. O’Brien’s ouster seemed to not only represent a sea change in CNN’s commitment to even the Nerf ball version of hard-hitting reporting, but it also left a hole for a resident race person.

If the motivation is to make a splash in a space not crawling with academics, Rhodes scholars, authors and researchers then the less contested space of public black conservative seems a good bet. Enter the culture-of-poverty arguments. They are convenient and have a receptive audience. As it turns out, when poor people are poor because they insist on making a poor culture there isn’t much we can or should do about poverty. Unfortunately, Lemon’s argument is like a lot of culture of poverty explanations for tragedy. It is stripped of empirical research. Time and time again research has shown that nothing about being poor or black or a single parent is as black and white as the Lemons of the world would have us believe.

All empirical evidence about grief and the loss of a child suggests that Peterson is likely doing a good job of blaming himself for the violent crime inflicted on his child. Yet, Lemon wants you to know how many children Peterson has, by how many mothers, and speculates as to whether or not Peterson had spent any real time with his child. Its unclear if the reader is supposed to blame Peterson for not being present or if it was the act of having the child itself that was the violation. It is unclear because Lemon is unclear if Peterson is like all the other poor black people that have children they cannot care for or if he is a wealthy superstar who provided for his child in ways most parents, of any race, can imagine. The only construct common to this muddled application of poverty culture to a rich athlete is that Peterson is black so Lemon focuses on that to the exclusion of logic, rhetoric, or decency.

All these insinuations fly in the face of what we know about grief, empathy and humanity. Lemon employs a decontextualized statistic about children of single parents but the fact is there is no evidence that grief is mitigated by the number of children one has, the number of parents with whom they co-parent, how much money they have, how poor they were raised, or how many times they have held their child. Indeed, it is absolutely possible to grieve for a child you have never held, even a child that is not your own. That’s called being a human being. Lemon’s argument, to the extent that there is a cogent argument, is that empathy for Peterson’s loss should be tempered with judgements about the authenticity of his grief by some arbitrary standard.

The only thing holding together these spurious insinuations of Lemon’s is an implicit assumption about the moral lives of people in those conditions. Whether it’s for ratings, for web hits or tally marks at the pearly gates, I cannot hazard an accurate guess. But, Lemon’s moralizing is as bitter as its namesake. Rather than asking questions about the morality of grieving parents perhaps we should ask why our culture rewards turning tragedies into morality plays where complex lives are erased in wars of good guys and bad guys.

McMillan Cottom is a Graduate Fellow at the Center for Poverty Research at UC-Davis. You can find her work at tressiemc.