“Sorry, I can’t bring my kids to your place if there are unsecured guns in the house.”

“Thanks for coming over. Do you mind leaving your shoes in the hallways and your pistol off my property?”

“I can’t stay over if you keep a gun in the bedroom, especially if we’ve been drinking. Guns make things less safe when the lights go out.”

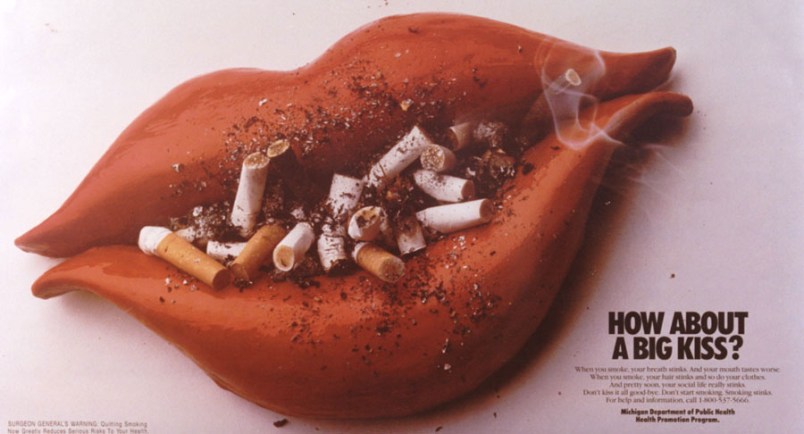

It’s surprisingly easy to imagine a society where gun ownership is looked down upon, if not scorned outright. This already happened with smoking, at least partly as a result of a public education campaign aimed at young people, and it happened when polite society finally came down against people flying the Confederate flag after the Charleston church shootings this year. Sometimes, when legislative action is difficult or downright impossible, a cultural approach works to curtail dangerous behaviors.

In short, we can make gun ownership uncool.

This was once unthinkable when it came to cigarettes. In post-World War II America, you might have kept an ashtray in your house even if you were a non-smoker, just to accommodate guests. It’s hard to imagine anyone doing that today, or even to imagine a smoker with the audacity to ask if they can light up inside.

The cool once associated with cigarette smoking, from James Dean rolling a pack into his shirtsleeves, to smoking Hollywood vixens, to outlaws like Hunter S. Thompson stuffing their cancer sticks into plastic filters, was effectively undermined by a public advocacy campaign started in 2000 by the American Legacy Foundation. These “Truth” ads, funded by money raised from the Master Settlement Agreement between U.S. tobacco companies, 46 states, five territories and the District of Columbia, focused on the behavior of tobacco companies over the years, casting young smokers not as rebellious outsiders but as dupes to a big money corporate system run by people who had lied for decades about the health risks of their products.

In its first two years, the Truth campaign helped reduce student-age smoking from one quarter of all high schools to 18 percent by the end of 2002. By 2009, it is estimated, the campaign generated health care savings that not only covered the costs of the outreach but allowed for between $2 and $5 billion in reduced healthcare spending. As Millennials, the original targets of the ads, grew up, they found new ways to rebel and now, instead of clustering outside the office in packs of smokers, they wear oversized headphones and pretend not to be able to hear you when you talk to them.

Like cigarettes, guns are big business. Smith & Wesson has a $1 billion market capitalization and a CEO who made $1.9 million last year. Sturm, Ruger & Co. has a $1.1 billion market cap and a CEO who made more than $1.1 million in the latest fiscal year. The National Rifle Association boasts 4.5 million members and regularly takes in contributions approaching $100 million a year, in addition to its program revenues. In short, guns are part of the establishment and people who spend money on them are no more iconoclasts than people who fork over money to Phillip Morris on a daily basis.

Like the tobacco industry, the gun industry has obfuscated about the dangers of its products. It has sold a fantasy of self- and home-protection that is out of touch with reality. And like tobacco companies, the industry aggressively markets to young people. A presentation by Smith & Wesson from March 2015 says that two thirds of new shooters are 18-34 years old, that a quarter of first time purchases by a second gun within a year, and that 60 percent of new shooters are buying for personal defense or security.

Of course, when Smith & Wesson presents, it talks about marketing to younger adults. In many parts of the country (including New Mexico, where I grew up and was first told a rifle was “mine” before I was 10) kids take ownership of guns well before they can drive. Keystone Sporting Arms still advertises its Crickett .22 caliber weapon as “My First Rifle” even after a five-year-old Kentucky boy killed his two-year-old sister with the single shot rifle he had received as a birthday present. They also offer a youth rifle called the “Chipmunk,” named for what kids are supposed to shoot with it.

The defense angle (whether self or society) is particularly vulnerable to clever media rebuke. There are the scores of dead children who have managed to get hold of the weapons kept by relatives. There are the sad tales of Oscar Pistorius and George Zimmerman. There was the well-intentioned gun owner who, during the heat of the shooting of Gabrielle Giffords, nearly shot an innocent bystander. There is probably no end of military and police veterans, highly trained and skilled with firearms, who will testify how even the most practiced shooter is vulnerable to involuntary behaviors during the height of a threat.

The gun industry has also made itself vulnerable to outright ridicule by opposing the most common sense reforms. The NRA opposes biometric trigger locks, for example, that would render weapons useless to anyone but authorized users because it fears it will lead to a ban on existing guns without such locks. The industry also opposes requiring gun owners to carry liability insurance. PSAs on such issues are unlikely to sway the current generation of gun enthusiasts but, as with smoking, it might be possible to get young people thinking early and viewing both the industry and culture of gun ownership more skeptically.

On the legislative front it seems America has made its choice and there is little chance for legal reform in the near future except at the margins deemed acceptable by the gun industry and a current generation of gun owners who believe that “things happen” is an appropriate reaction to gun deaths. When lawmakers can’t lead, a social solution is certainly worth a shot.

Photo Credit: Brogan & Partners

Michael Maiello is a playwright, author and essayist. He has written for Esquire, McSweeney’s, The Daily Beast, Reuters, Forbes and theNewerYork.

Great idea. I’ve been doing this for years on my own to a lesser degree, mainly by telling people I don’t want them to bring guns into my house, ever, as well as leaving where I’m at abruptly when anyone pulls out a gun.

I think it could work.

I agree with the hope behind the thought, but in this case I think you’re fighting a cultural force that far outweighs smoking. Cigarettes gained their cool, sophisticated image from movies, but they were rarely central to the plot and action. Guns have always been the go-to solution in movies, and have set an image that not only do they solve problems you look cool solving them.

I can only think of one movie I’ve ever seen during which a gun was brandished and never fired. That’s a hard momentum to overcome, and would take multiple generations to do so. Still, I agree with @TeenLaQueefa - I’m doing my part one step at a time

Have a Life problem? Get a gun!

I’ve been advocating for this approach for years. If we can make cigarettes…or littering (for instance)…socially unacceptable, we can surely do the same with gun possession.

This is the single thing we could do that would be most likely to have a real effect. I argued exactly this in some comments yesterday. This approach has not only worked with smoking, it has also worked with drunk driving, which used to be seen as no big deal. Also, the anti-obesity campaign has reduced soda consumption significantly and the rise in obesity seems to have stopped and even to be reversing.

The gun fetishists use (and misuse) the 2nd Amendment. Let’s use the 1st Amendment against them.