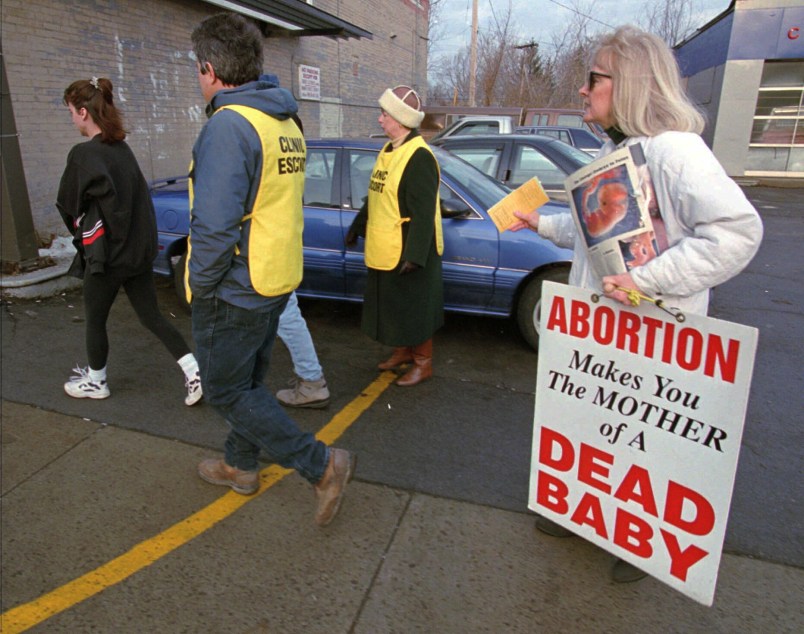

Before Massachusetts law established a 35-foot buffer zone outside of family planning clinics, protesters dressed as the grim reaper and holding scythes would approach patients, shout threats, and literally stand between a patient and the entrance to a clinic. The opponents of buffer zones claim that they have a right to “counsel” women within this zone.

But what anti-choice protesters do outside of abortion clinics has never been counseling, which involves facts and occurs with trained medical professionals. Since the establishment of buffer zones in our state in 2007, medical professionals have seen real improvement in the atmosphere around freestanding clinics. Patients are no longer spat on and the yelling is a little quieter. Women and their families feel less afraid and are at less risk of a physical altercation on their way into a clinic.

This spring, the Supreme Court decides if Massachusetts’ buffer zone law is constitutional. Buffer zones were created in Massachusetts after a shooting rampage at two abortion clinics in the Boston area left two clinic workers dead and five injured. The high court is contemplating whether a protester’s freedom of speech in the 35-foot zone outweighs the right of patients to enter a health care clinic safely. While security has improved at our reproductive health clinics, violent protesters and aggressive tactics are not a thing of the past. The zones must remain in place to protect the safety of patients and staff.

As a family doctor who provides primary care for the entire family, I want to bring to the forefront an issue that has not been part of recent discussions of buffer zones. The reason we need buffer zones is that in most U.S. communities, freestanding clinics are the only providers of abortion care. These clinics provide outstanding care, but their visibility and accessibility make them easy targets for protesters. It has become clear that we need to expand where and how women can access abortion care, and this must include primary care providers’ offices. This is a setting in which women could receive safe first trimester abortion care just as well as in dedicated family planning clinics.

Some women will always prefer going to dedicated family planning clinics and these clinics will always be there to provide excellent reproductive health care. But I also have patients who would like to be able to get their contraception, prenatal care, and abortion care from the same doctor who they go to for migraine treatment or their children’s vaccinations. And certainly one of the reasons some of these women would like to be able to have their family doctor perform their abortion is that this would give them a greater level of privacy surrounding this personal medical decision by allowing them to avoid walking through a gauntlet of protesters outside of a clinic.

Yet there are currently significant challenges to family doctors’ ability to provide abortions in a primary care setting: difficulty in obtaining abortion training, increasing affiliations with Catholic health systems, and a growing number of state laws seeking to restrict abortion access by targeting abortion providers in any number of punitive ways. But integrating abortion care into family practice is possible, and successful programs exist to help primary care clinicians do this.

Freestanding reproductive health clinics remain the cornerstone of abortion access in the U.S. today and all medical professionals must defend our colleagues who work in them and the women they serve. Many of these nonprofit clinics also meet more than just the reproductive health needs of patients. They serve as primary care providers for low-income and uninsured women, offering free care and sliding fee scales for cancer screenings, as well as diagnosis and treatment of other medical conditions like urinary tract infections or thyroid disease.

Increasing women’s options for accessing comprehensive reproductive health care should be supported by anyone who cares about women’s health. We can achieve this by increasing the number of primary care providers who are able to offer abortion care within their offices and by defusing the tactics of protesters who seek to prevent women from accessing constitutionally protected medical care. If a woman cannot receive comprehensive reproductive health care in her primary care office, she should be free from intimidation and violence while seeking that care elsewhere. I hope the Supreme Court justices understand what is at stake in this case and decide to uphold Massachusetts’ buffer zone law.

Dr. Julie Johnston is a family physician in Massachusetts. She received her medical degree from Brown University Alpert Medical School.