For as long as I can remember, I’ve been pro-choice. And for as long as I can remember, I’ve been in pain, thanks to nerve abnormalities in my face and head that I was born with, and severe wrist problems that started in my late teens.

There’s no correlation between being in favor of reproductive rights and having chronic pain. But these issues have a great deal in common, such as the questions of bodily autonomy, patient dignity, and stigma. Chronic pain may not stir up religious passions, but it it is almost as politicized as abortion, falling in the orbits of the war on drugs, women’s health, stigma, and the Republican backlash against Obamacare.

Some of the same things that make chronic pain a challenge for medical practitioners also make it a problem for politicians and administrators concerned with health care policy. Because chronic pain doesn’t show up on an X-ray or a blood test, it’s hard to know who needs treatment and who doesn’t. In an ideal world, the simple solution would echo the pro-choice slogan “trust women” — just trust the patients to be honest about how much and what sort of treatment they need.

But just as too many women find their judgment questioned when they choose to terminate a pregnancy, too many chronic pain patients are greeted with suspicion when they ask their doctor for a refill of Percocet or Valium. Neither our current medical establishment or political climate are well-equipped to see shades of grey when it comes to patient care and trust, but in chronic pain as in abortion, patient-centered care is more critical than ever. On paper, my list of medications is daunting and a little alarming; in reality, those medications are what allow me to live an independent life. On paper, a request for a mid-second trimester abortion, or a third abortion, or an abortion for someone who already has children, could stir up all kinds of judgment and assumptions; but the reality is always more complex.

Not all chronic pain sufferers encounter such obstacles to treatment, and not every woman that needs abortion care runs into political and financial obstacles. But getting comprehensive care in either circumstance can be challenging, to say the least. I’ve lost count of the number of times doctors have just suggested that I should just learn to live with my pain, or not use my hand so much, or be more patient. The practical repercussions of these incorrect diagnoses were that treatment was delayed for very real physical problems. But their broader implications — that I don’t know my own body, that a stranger knows what is best for me — strongly echo both the pre-Roe mentality of hospital abortion committees and the post-Roe patronizing grandstanding of anti-choice politicians.

Caitlin Caven knows this connection firsthand. After being diagnosed at age ten with Crohn’s disease — a poorly understood, often stigmatized and, in her case, exceedingly difficult to treat condition — Caitlin became involved with reproductive rights. “A lot of it has to do with bodily autonomy,” she tells me. “I don’t want to be overdramatic about it, but I think in some ways, I gave [my autonomy] up at a really young age, at the hands of the medical system. And that’s right at the center of the reproductive rights debate, where you have one side that thinks they know better than you what should be done to your body. I think that that is what really hit a nerve in me. That’s just absolutely not okay.

“It’s hard for me to say why reproductive rights and not advocating for Crohn’s patients, or advocating for chronic pain,” Caven admits about her chosen field of activism, which included being an abortion doula with New York City’s The Doula Project. “I don’t know why it landed quite the way it did. But I think some of it is that there’s so little support and so much stigma around abortion, and that’s what really drew me in. I’m pretty lucky to come from a family that is just so supportive of my decisions in health, and I wanted to be able to potentially provide support or a normalizing influence to somebody who might not be able to get that support at home, or might not be able to tell anybody because of how deeply stigmatized the issue is. But I also think that, on a pragmatic level, nothing surprises me anymore. I’m not grossed out by blood, I know what that fear going into a procedure feels like, I know the fear of the unknown, the fear of pain. I recognize that nervousness. I feel like my experiences made me more empathetic and compassionate than maybe I would have been otherwise.”

And that might be the most powerful, and least tangible, connection between chronic pain and reproductive rights: that behind the political rhetoric, imperfect medical systems, and societal judgments are actual people who deserve to be treated with dignity and respect.

Sarah Erdreich is the author of Generation Roe: Inside the Future of the Pro-Choice Movement. She lives in Washington, D.C. with her family.

—

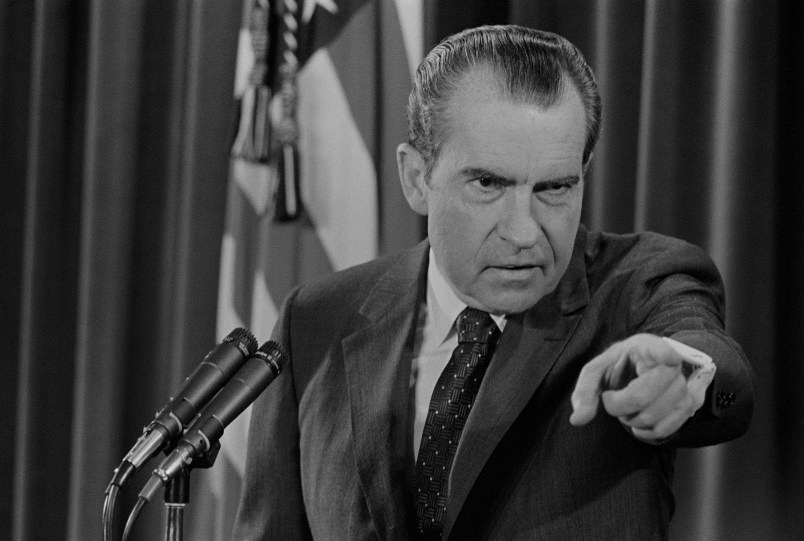

Photo: Shutterstock/KieferPix

So true. There’s still a huge medical constituency that views pain-control as “drug-seeking”. And a regulatory environment where doctors who have chronic-pain patients are often under legal scrutiny. (Which also ties in with the general winner-take-all culture where someone who can’t “power through” everything is considered a less-worthy person.)

And, anecdotally, another tie-in: pain after an abortion procedure treated with regular-strength tylenol.

Interesting and troubling similarities between the judgments and other challenges faced by women seeking abortions and those faced by patients suffering from chronic conditions. I think trust and compassion are helpful prescriptions for anyone navigating a complicated health issue.

FWIW, Katie McCurdy shared some interesting notes and images this morning in a blog post about visualizing the context and complexities of patients managing chronic conditions that may be of interest in this regard.

Just more punishment for women - my dentist offered my choice of Vicodin or Tylenol 3 for a root canal.

The difference is that there really are drug addicts who claim to have chronic pain, precisely because they can fake it and get prescriptions (though usually they don’t have to be very convincing because the doctors are complicit). Not that that makes it any easier to genuine chronic pain sufferers, but it is a real problem. With abortion, there’s no one trying to get a scam abortion who doesn’t need one.

Ah, but… how many people are there with chronic pain, versus how many who are drug-seeking?

This is somewhat akin to the argument that it’s more important to focus on false accusations of rape, than of actual rape.