This article is part of TPM Cafe, TPM’s home for opinion and news analysis.

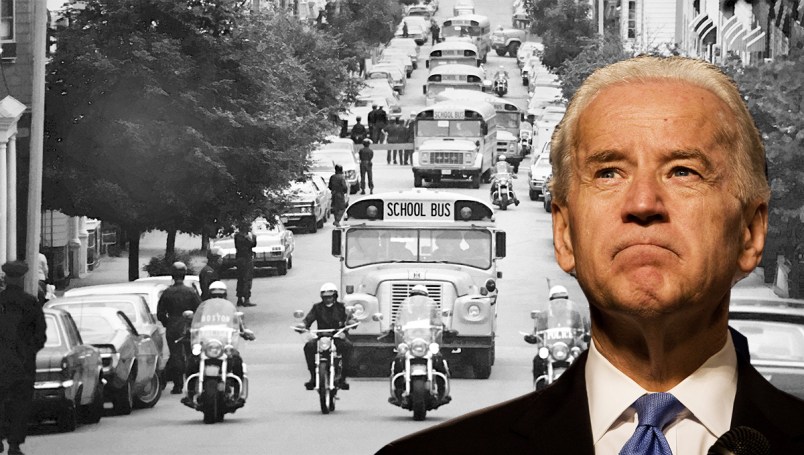

Joe Biden’s opposition to busing for school desegregation in the 1970s reveals how white liberalism played a central role in defending suburban racial and class privilege against civil rights challenges. The controversy also exposes the hypocrisy of those who draw a sharp historical distinction between “de jure” (legal, state-mandated) segregation in the Jim Crow South and “de facto” (allegedly private and market-based) segregation in the North and West.

In pursuit of the Democratic presidential nomination, Biden has defended his civil rights record by claiming that “I supported busing to eliminate de jure segregation” while simultaneously arguing that “busing did not work.” Both of these statements are clear distortions of the historical record during the civil rights era.

As a senator from Delaware, Biden repeatedly sought to block the executive and judicial branches from implementing the constitutional remedy of busing to overcome de jure segregation outside the South, including a 1975 federal court order to consolidate the public schools of Wilmington with its surrounding and almost all white suburbs. And despite the popular mythology that busing was a disastrous public policy failure, the court-ordered technique of inter-district or metropolitan-wide desegregation through two-way busing between majority black urban schools and their overwhelmingly white suburban counterparts successfully minimized white flight and produced significant levels of racial integration in more than a dozen large southern districts — and in the border South cities of Louisville and Wilmington.

In the 1970s and early 1980s, Biden’s political crusade against busing “outside the South” was based on a false regional dichotomy that attempted to redefine state-sponsored segregation in the public schools and housing markets of the metropolitan North and West as legally innocent, de facto racial imbalance beyond the reach of constitutional law. Much of the recent coverage of the Biden controversy has reproduced this artificial de jure versus de facto regional binary and therefore ignored or underplayed several key historical developments in court-ordered desegregation in Delaware and the broader struggle for racial justice in modern America.

Delaware had Jim Crow school segregation

Delaware’s contemporary, widely accepted classification as a northern state demonstrates the selectiveness of popular historical memory of the civil rights era. In the mid-twentieth century, Delaware was a border South state that enforced statutory Jim Crow segregation; in fact, a lawsuit against separate-and-unequal schools by African American parents in Wilmington became one of the five cases consolidated in the Supreme Court’s landmark 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision. After Brown, the Delaware state government adopted a gradual desegregation technique known as “freedom of choice” that placed the full burden of integration on African American transfer students, and this soon became a model for tokenist compliance in the urban South.

In Wilmington, the school board also gerrymandered attendance zones to reproduce segregated housing patterns, a policy of deliberate racial discrimination practiced in every large urban district across the nation during the twentieth century. In 1974, a federal district court in Delaware found that “all of the pre-Brown colored schools that remained open continued to be operated as virtually all-black schools,” which constituted a “clear indication that segregated schooling in Wilmington has never been eliminated and that there still exists a dual school system.”

States outside the South got a pass on mandated desegregation for decades

In the early 1960s, the NAACP launched a major legal campaign against school segregation in the North and West, especially by highlighting the intentional gerrymandering of school attendance zones to reinforce neighborhood housing patterns. Yet the federal courts generally declined to order remedies for allegedly “de facto” school segregation resulting from housing segregation, euphemistically labeling this a “racial imbalance” in public education.

In Congress, the liberal sponsors of the 1964 Civil Rights Act secured passage only after explicitly seeking to exempt northern and western communities from the scope of executive branch enforcement of Brown by stipulating that “‘desegregation’ shall not mean the assignment of students to public schools in order to overcome racial imbalance.” Border states such as Delaware quickly sought to reclassify segregated black schools in urban centers as a problem of racial imbalance resulting from housing patterns that would therefore be outside the scope of judicial remedy.

In the recent Democratic debate, when Biden claimed that “what I opposed is busing ordered by the Department of Education,” he was operating within this deep history of white liberal maneuvering to restrict federal civil rights enforcement in the area of public schooling to the Jim Crow South (alongside continued amnesia about Delaware’s central role in Brown).

1971 decision opened the door to busing remedies for segregation outside the South

The NAACP’s 1971 Supreme Court victory in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg upended the prevailing distinction between de jure and de facto segregation. The decision upheld a district court ruling in North Carolina that busing was an appropriate legal remedy to overcome “neighborhood schools” that reinforced state-sponsored patterns of housing segregation, such as exclusionary municipal zoning, federal subsidies for all-white suburban developments, and inner city site selection for public housing.

The NAACP immediately moved to apply the Swann verdict to urban districts nationwide by challenging their “neighborhood schools” assignment policies as an unconstitutional approach based on officially sanctioned, and therefore de jure, segregation. President Richard Nixon then attempted to limit the reach of Swann with a policy statement that rejected the “compulsory busing of pupils . . . for the purpose of achieving racial balance” by insisting on the “fundamental distinction between so-called ‘de jure’ and ‘de facto’ segregation . . . [that] results from neighborhood housing patterns and does not violate the Constitution.”

But many federal courts rejected this fraudulent historical argument perpetuated by the Nixon administration and soon to be embraced by Joe Biden as well. In 1974, a three-judge panel in the Evans v. Buchanan litigation ordered the Wilmington school board to comply with Swann based on its “affirmative duty to eliminate from the public schools ‘all vestiges of state-imposed segregation.’”

That same year, then-Sen. Biden and a number of other liberal Democrats in Congress who had previously supported comprehensive desegregation in the South joined with longtime racial conservatives to vote for a series of legislative amendments designed to limit federal funding for busing aimed at overcoming racial imbalance.

A 1975 ruling acknowledged Delaware’s history as a Jim Crow state and mandated integration

In Milliken v. Bradley (1974), the Supreme Court overturned a metropolitan busing plan covering the city and suburbs of Detroit, a devastating civil rights defeat that resurrected the de facto mythology of white northern innocence and exempted most northern and western suburban areas from the Brown decision. However, the concurrent school desegregation litigation in Wilmington resulted in a different outcome in large part because of Delaware’s statutory history as a Jim Crow state.

In 1975, a district court panel in Evans v. Buchanan ruled that the Delaware state government and the suburbs of New Castle County (95 percent white) shared legal responsibility for maintaining racial segregation in — and promoting white flight from — the Wilmington city schools, which had shifted from 72 percent white in 1954 to 83 percent black two decades later. Circumventing the restrictive Milliken standard, the Wilmington decree held that “de jure segregation in New Castle County was a cooperative venture involving both city and suburbs.” The court ruled that municipal, state, and federal agencies all contributed to the racial segregation of metropolitan Wilmington through formal actions ranging from doling out housing subsidies to all-white suburbs, locating public housing in a way that concentrated poor and minority families and employing student transfer policies that exacerbated white flight.

As a remedy, that judicial panel in Evans v. Buchanan ordered the consolidation of the Wilmington schools with the adjacent suburban districts to facilitate racial integration through a comprehensive busing plan.

Biden opposed busing despite 1975 court finding on de jure segregation in Delaware

Under pressure from Wilmington’s white suburbs, Biden promptly assumed a leading role in the national political resistance to court-ordered busing, as Brett Gadsden has chronicled in Between North and South: Delaware, Desegregation, and the Myth of American Sectionalism. Between 1975 and the early 1980s, Biden repeatedly sponsored legislation to restrict the authority of the federal government to order busing as a desegregation technique to redress entrenched segregation in neighborhood schools.

The historical record contradicts Biden’s recent insistence that he only opposed busing ordered by the executive branch to overcome racial imbalance and other forms of de facto segregation. The same year as the Wilmington consolidation order, Biden urged the Senate to find a way to “prevent the courts from ordering busing,” which by definition involved a factual finding of state responsibility for segregated schools. He also continued to insist that racially isolated schools in urban centers were the products of de facto segregation, notwithstanding the federal judiciary’s explicit finding of a comprehensive history of de jure segregation in New Castle County, Delaware.

In these efforts, Biden effectively sought to force the federal courts to apply the Milliken standard to Delaware by redefining its racial history as northern de facto-style segregation, which would have prevented the implementation of the inter-district busing plan in metropolitan Wilmington. Although he did support other aspects of the civil rights agenda, and often justified his position based on the reluctance of African American families to send their children to faraway schools, Biden’s anti-busing stance most vividly reflected the political resistance to meaningful levels of integration in the white suburbs of Wilmington and across the nation.

In 1977, the same year that Wilmington implemented the court-ordered consolidation plan, Biden warned that busing would cost liberalism “the basic support of that so-called great unwashed middle class — of which I am a part,” as Gadsden documented in his book. In response, the head of the U.S. Civil Rights Commission called Biden’s legislative efforts to forge an alliance between northern liberals and racial conservatives “unquestionably the most sweeping attack on a civil rights act passed by the Senate in recent years.”

Metropolitan desegregation through busing worked

The Supreme Court ultimately upheld the metropolitan busing plan in Wilmington, despite its striking similarities to the Detroit city-suburban consolidation formula overturned in Milliken, because Delaware was “southern” enough to overcome the de facto mythology based on its status as a Jim Crow state in 1954.

The consolidated urban-suburban busing plans implemented in southern cities such as Charlotte and in border cities such as Wilmington proved to be the most effective desegregation technique in countering the de jure fusion of school and housing segregation that shaped every metropolitan region in the United States.

Court-ordered busing to integrate white neighborhood schools and overcome suburban patterns of housing segregation was also extraordinarily unpopular, including among many white liberals and most elected officials of both parties, because the policy represented a fundamental and unprecedented civil rights challenge to the metropolitan landscape that sustained white class privilege. Rather than debating whether or not Biden’s anti-busing collaborations with southern segregationists reveal personal racism, it is more useful to emphasize that his policy stance of protecting white suburban schools from meaningful integration stood squarely within the political mainstream, both then and now. The Biden controversy exposes the considerable gulf between the anti-racist agenda of civil rights organizations and the political culture in which white liberalism and conservatism overlap.

Matthew D. Lassiter is Professor of History at the University of Michigan and author of “The Silent Majority: Suburban Politics in the Sunbelt South“ (Princeton University Press).