We’re asking our fellow TPMers to share their own personal reading recommendations: books they love or that have shaped their lives.

Comment below with some of your favorites! Also, you can always purchase any of the books by visiting our TPM Bookshop profile page.

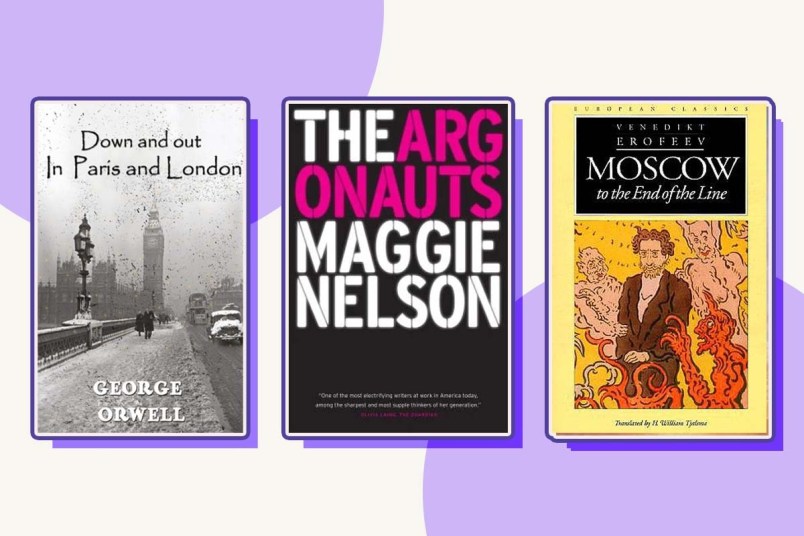

Investigative reporter Josh Kovensky is up this month. Check out his list of five books that always offer him something surprising and new.

It’s easy to get bogged down, for one day to melt into another.

But I’ve found that some books continue to jolt me awake, no matter how much time has passed and regardless of how many times I’ve read them. Either through narrators who don the life of another, struggle to survive through dizzyingly fast social changes, or choose to renounce it all, erasing their own consciousness in bottles of shoe polish hooch, these books remain startling in the best possible sense of the word.

Below are five books that always offer me something surprising and new.

Moscow To The End Of The Line by Venedikt Yerofeyev

Moscow To The End of The Line is something like a Soviet answer to Hunter S. Thompson. Originally published via Samizdat, the book is narrated by a 1960s construction foreman who gets fired from his job and begins to wander Moscow in search of the Kremlin, before slowly drinking himself into oblivion on a regional commuter train to his hometown of Petushki (his hometown means “fighting cocks” in Russian, which lends itself to the book’s original title: Moscow – Petushki).

The further the train goes from Moscow, the deeper we get into the narrator’s hallucinations and his observations of Soviet society. He gets more desperate himself, drinking homemade shoe polish liqueur along the way and holding court with seemingly imaginary interlocutors. It reads as if you yourself have taken a shot of shoe polish — a story that’s fantastic on the surface but deeply violent underneath, an epic of one person trying to mount a psychological escape from a society in which he’s physically trapped.

Free by Lea Ypi

This memoir recounts Lea Ypi’s upbringing in Albania under the Stalinist regime of Enver Hoxha. She grows up a devout communist, only to discover as the regime fell in the early 1990s that her world — and family — was based either on lies or distorted by untold secrets. As it turns out, Ypi was from a family of dissidents descended from a pre-Hoxha fascist politician, a fact that forever limited her father’s advancement and which resulted in the imprisonment of some of her relatives and her family’s acquaintances. The narrative splits along these two ruptures: in history, and in Ypi’s own life. That extreme change allows her to ask deeply bracing questions about the two systems’ limitations with a level of clarity that’s both rare and jolting.

Down and Out in Paris and London by George Orwell

This classic involves George Orwell allowing himself to descend into poverty, essentially to see what it’s like being “down and out.” He gets a job as a dishwasher in a restaurant run by Russian emigres, working seventeen and a half hour days, at times without pay. His luck turns for the better in a sense after a friend helps him move to London, where Orwell becomes a tramp, wandering to Salvation Army shelters and hostels. The book is hilariously written, and is also partly a farce: Orwell had the family and connections to remove himself from the situations he encountered at any time. What Orwell experienced was not true poverty in that sense. But as a record of forcing yourself to live in an environment that’s completely foreign to you by birth and upbringing, it’s a fascinating and visceral one.

The Argonauts by Maggie Nelson

It’s really hard to classify this book, a mixture of memoir, literary theory, novel, and lyric poem. But it’s basically a love story, one that consciously tries to transcend various gender and family norms as Maggie Nelson meets and marries her transgender partner Harry Dodge. The narrative is feverish as much for the intensity of the language she uses as it is for the boundaries that Nelson is constantly trying to cross, or expose as illegitimate. What results is a book that’s strangely renewing, powered by a narrative that’s equal parts energetic and tender.

The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle by Haruki Murakami

Outwardly, very little happens in this book. The main character quits his job at the start, and spends most of the rest of the novel alternating between lying around at home, wandering around Tokyo, and sitting at the bottom of a well. But throughout, we get glimpses of an underworld that begins to creep towards the narrator: through parallel narratives set in Japan’s World War Two client state in Manchuria, snippets of newspaper articles, and the narrator’s own hallucinatory travels from the well’s bottom. It’s not entirely clear how we get there, but through a combination of self-abnegating psychedelic trips the narrator ends up somewhere new, with a sense of possibility.