If you want something done right, do it yourself, the old adage goes.

But whether that adage can apply to election systems is a major question in the voting rights world and one that Los Angeles County will be trying to answer this election cycle.

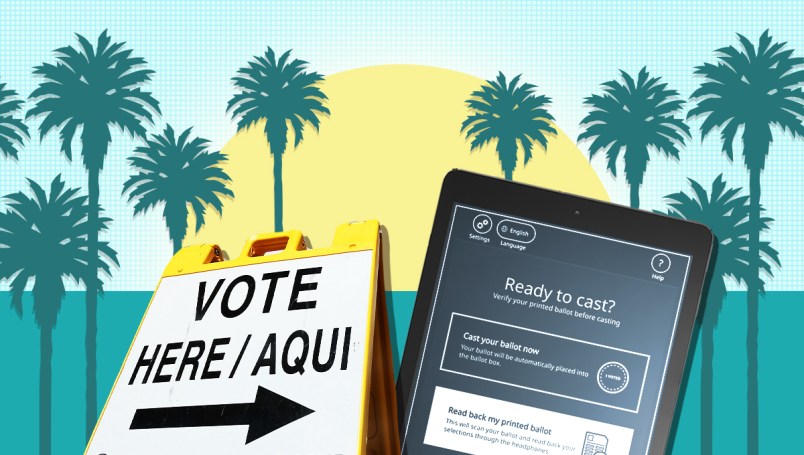

With in-person primary voting starting in earnest on Saturday, L.A. County is rolling out a comprehensive overhaul of its election system that was more than a decade in the making and that costs some $300 million.

In a first, the system is entirely publicly owned, meaning that all of the equipment was commissioned and is controlled by the local government.

The stakes for L.A. were always going to be high, given the county’s massive and incredibly diverse population. The county has 5.4 million registered voters, more than 42 states.

Recent debacles in other primary elections have only added more scrutiny, and the technology is being launched at a pivotal time in the Democratic presidential primary.

The new system has been praised broadly by election administration wonks, some of whom having advised the county directly on the overhaul. But it has also attracted criticism from some security experts, while prompting a lawsuit from one of L.A.’s cities.

“The problem is that there are just unsolvable technical difficulties in trying to create a one-size-fits-all system,” said Philip Stark, a professor at U.C. Berkeley who has warned there is a “perfect storm” of things that could go wrong.

Voting Solutions for All People

A major focus of the overhaul was to create a system that was more accessible for the county’s millions of voters while also having the capability to evolve with the shifting needs of L.A.’s changing demographics.

The technological improvements come as L.A. also moves to a so-called vote center system, which will replace the traditional precinct-based model. In doing so, L.A. is reducing the number of polling places, in favor of larger, more sophisticated vote centers, where voters from any precinct in the county can go to cast their ballots.

While voters in other states have benefitted from a switch to vote centers, they have also sometimes caused confusion and long lines, as was the case in Arizona’s 2016 Democratic primary. California also offers a mail-in ballot option, which more than half of L.A. County’s voters has requested to use.

Once a voter shows up to a vote center, she will be given a ballot with a special barcode that will tell the voting machine — a tablet resembling an iPad — which of the county’s 524 different ballot-types for the March primary should be brought up. The voter will also have the choice of 13 different languages, and the tablets have been equipped with several features (an audio function, adjustable font and contrast, a braille keyboard, among many others) that will make it easier for voters of all abilities to submit their selections.

“It was so intuitive to interact with,” said Tammy Patrick, an elections expert at Democracy Fund who participated in a demonstration of the system. “It works like the technology that we’re accustomed to in our day-to-day life.”

The system is called Voting Solutions for All People (VSAP), as it has been designed with needs of people of various abilities in mind and because all voters can use the same equipment.

“It’s an inclusive voting experience for every voter, no matter if you have a disability or if you don’t,” said Gabe Taylor, a voting rights advocate for the nonprofit Disability Rights California, which worked with the county to design the system.

‘It Leaves The System Vulnerable’

Those who have criticized the system have no doubts about the county’s good intentions, but their skepticism arises from the larger debate over the use of so-called ballot marking devices (such as the VSAP tablets) versus equipment that requires voters to mark a paper ballot with their own hands.

L.A. County’s new system creates a paper trail by printing out a paper ballot for the voter to examine herself before she submits it. The problem, according to Stark, is that if a voter does see an issue on her paper ballot, there’s no way for the poll worker to know if the discrepancy is the result of user error or was caused by some malfunction of the machine, including malfunctions caused by a bad actor.

Stark and other critics, including Sen. Ron Wyden (D-OR), have argued that ballot marking devices should be available for those who need them, but that hand-marked paper ballots should be the standard offer to voters who can vote that way.

There are other aspects specific to L.A.’s system that have attracted scrutiny. Some have taken issue with the so-called “poll pass” feature, which allows voters to bring with them a pre-made barcode that they can scan at the tablets to automatically make all of their choices.

Compared to the rest of the system, “poll pass has not been thoroughly tested or reviewed,” said David Holtzman, the former head of L.A.’s League of Women Voters, adding that “it leaves the system vulnerable to a few problems.”

Additionally, the county was sued by the city of Beverly Hills for the way the system deals with contests that have more than four candidates. The tablets use a “more” button to bring up the next page of four candidates, which, according to the lawsuit, creates “a significant electoral disadvantage” for candidates listed on later pages compared to those listed on the first.

The “more” button issue was also highlighted as a concern by California Secretary of State Alex Padilla during the certification process. California law required that L.A. County, like private vendors, go through the state’s certification process, perhaps the most rigorous in the country.

All in all, in Padilla’s approval of the system, he listed about three dozen conditions for the approval, spelling out several aspects of the system that L.A. County will need to continue to work on fixing or improving. Among the conditions was that the county make available hand-marked paper ballots at vote centers, which was something that the county initially sought to avoid.

VSAP’s critics pointed to the sheer number of conditions as reason to be worried about the system, though an official in the secretary of state’s office told TPM that every certification that’s issued is conditional.

Ironically, the transparency of California’s certification system — and of L.A.’s overhaul process more broadly — may have further opened the new system to criticism.

Justin Levitt, a Loyola Marymount law school professor who advised the county on the overhaul, said that the criticisms came down to trade-offs that are inevitably involved in a project like this.

“I don’t mean to minimize the concerns that people are raising, but in order to eliminate them entirely you’ve got to trade off something else,” Levitt said. “From my view, the risk of the problems manifesting isn’t worth the trade-off to me.”

‘A Game Changer in the Marketplace’

Despite the criticisms, VSAP’s designers and supporters are heading into this month’s primary with confidence because of the intensive process the county went through in creating and testing the system.

Seeking to replace equipment dating back to the 1960s, L.A. started the initiative in 2009, as it struggled to find a private vendor that offered a comprehensive system that could address the county’s complicated needs.

Mike Sanchez, a spokesperson for County Registrar-Recorder, said officials began designing the system in 2014, and have continued to refine it based on stakeholder feedback as recently as this year. Testing for the system included a pilot election in a municipal contest in November.

“They planned to give it enough time to work,” Levitt said, avoiding the temptation to focus on short-term fixes to the detriment of a longterm solution.

Beyond just the example the county set in its process, there are other ways VSAP could be “a game changer in the marketplace” for the elections systems industry, as Patrick put it.

L.A. County has said it intends to make the technology available for other jurisdictions to use and experts generally expect that the overhaul will put more pressure on the election equipment industry — which is currently dominated by a few private vendors not known for their transparency — to innovate.

“In some ways, there’s nothing revolutionary about VSAP,” said Whitney Quesenbery, co-director of the Center for Civic Design, who sat on an advisory board for the project. “And in other ways, what’s revolutionary is how well they put it together.”