Even if they don’t practice in an area particularly hard hit by the coronavirus, the pandemic is already at every primary care doctor’s doorstep.

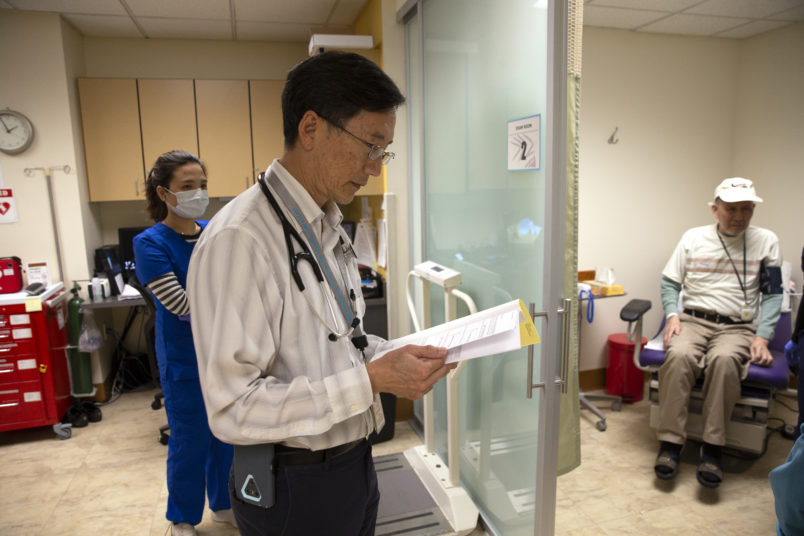

As hospitals buckle under the pressure that COVID-19 has placed on their facilities, primary care doctors across the country are facing their own challenges in adapting to an approach to care where patients, as well as their staff, are discouraged against leaving their homes.

Whether they’re in areas where the virus has spread significantly, or those regions that remain relatively isolated from the outbreak, these physicians have had to make drastic changes to how they operate their practices.

“We are being exposed to a new way of practicing medicine,” said Dr. Nikhil Hemady, the chief medical officer of Honor Community Health, which is near Detroit. “The way I look at it is that we are at war. We are truly practicing medicine like we are at war.”

In interviews with TPM, primary care providers from across the country described an increasingly perilous situation, whether they practice in family-style clinics, community health centers or ambulatory facilities. They’ve recounted layoffs, furloughs and cutbacks to hours they’ve had to impose just a few weeks into the current pandemic. Their patients have struggled with the new technology doctors have had to adopt to deliver care. Their staff fear contracting the virus themselves, as they face the same shortfall in protective equipment that is currently plaguing larger health care systems.

These practitioners worry not just about facing the current crisis, but whether their clinics will still be standing when the United States makes it to the other side of the pandemic.

“Primary care is hard to keep afloat in the best of times,” said Christi Siedlecki, the CEO of Grants Pass Clinic in southern Oregon. “This is really scary.”

Siedlecki did the best she could to prepare for how the outbreak would upend her clinic’s operations, but the changes to the medical landscape arrived before she could find her footing.

For the last month or so, she knew COVID-19 was coming in only a matter of time. Her community is right on I-5, the main thoroughfare between Washington and California, and positive cases have been confirmed in counties surrounding hers.

About three weeks ago, preparing for the outbreak became “all consuming,” she said. By the time another week went by, her clinic had seen a “significant” drop of in-person patient traffic that is the source of most of its revenue.

“No sooner than when we were putting forward our first efforts to get organized, it got real and it got real, fast,” Siedlec said.

Splinting Wrists While Patients Stay In Their Cars

Perhaps the biggest challenge primary care doctors are facing is the need to discourage all unnecessary in-person interactions to stem the spread of the virus. This effort is particularly crucial at health care facilities, where the most regular patients can also be the most vulnerable to COVID-19: older people and those with chronic conditions.

These primary care providers are also serving as a frontline defense against the virus, as they are where those exhibiting symptoms go for assessments and in the hope of getting still-elusive tests.

“I’m very concerned about our patients with chronic conditions and things that we would usually be managing aggressively,” said Dr. Jennifer Aloff, of the Michigan practice Midland Family Physicians. “They’re doing the right thing by staying at home, but I am concerned about how we will handle the deluge when things return back to normal, whenever that may be.”

Some practices have reworked their operations to adapt to this conundrum. Aloff described scheduling visits for relatively healthy patients in the morning, and sick in the afternoon.

The staff has also delivered infant immunization shots and splinted broken wrists while their patients remained in their cars.

“We are trying to meet patients’ needs however the patient is comfortable,” she said.

More broadly, the situation has necessitated the expansion of what’s known as “telehealth” — i.e. consultations conducted through electronic communication platforms — as well as less technologically-advanced methods of delivering care, such as in video chats and phone calls.

While prudent for protecting the public health, this shift has presented a range of obstacles practically overnight that doctors have had to grapple with

Clinics have had to quickly scale up their technology platforms at a time that telehealth technology contractors are slammed with requests for assistance.

They’ve had to buy new equipment — such as laptops, so staff can work from home, or new phones, so they don’t have to give out their personal numbers to patients — just as their revenues are drying up.

Meanwhile, patients have had their own issues with adapting to the new systems. Older patients in particular are known to struggle with the technology, and due to the self-isolation the outbreak requires, they can’t have their younger relatives come over to set the services up. Others, especially lower-income patients who may rely on community health centers, don’t have consistent internet access at all.

Doctors have tried to make the technology more accessible — for instance, by switching from an app a user must download to a web-based link they can send to patients via texts.

But often, clinics are just relying on audio-only phone calls to advise and treat patients, a form of care for which they’ll get extremely low reimbursements, if any at all.

A Major Drop Off In Appointments

The financial realities of this new environment have turned a challenging time for many clinics into a fullblown panic.

For primary care doctors, their financial model is built around the money they take in for in-person visits. The Trump administration has loosened the rules around telehealth and virtual visits in a way that has made it easier for doctors to be paid for that type of care, through federal health care programs like Medicaid. But they’re often still taking a haircut, even in the most generous categories of those reimbursements. Some private plans have not followed the federal government’s lead in expanding clinics’ ability to bring in revenue via telehealth, policy experts told TPM.

Doctors and policy experts said that many primary care practices were seeing a 50-60 percent drop in business in recent weeks. Aloff said that the number of patients her clinic is seeing has dropped around 95 percent, and that included telehealth appointments.

This dire financial situation has led to clinics making tough choices to make ends meet. Already, there have been layoffs, as well as efforts to reduce the hours of staff. The need to quarantine several staffers who are feared to have come down with the virus has also reduced payroll costs for some practices.

Honor Community Health closed 14 of its 16 locations for in-person visits, according to Hemady. (Eight of those locations were at schools that were closed for the outbreak.)

But even with this drop of in-person traffic, primary care physicians are still struggling with a shortfall of personal protective equipment, such as gowns, masks and goggles that will protect staff from contracting the virus and spreading it to other patients.

The “disjointed” distribution network for that equipment — as well as for COVID-19 tests and other supplies — means that the “smaller entity, the longer it takes to get things to them,” according to Shawn Martin, the CEO designee of the American Academy of Family Physicians.

Aloff recalled a lucky break that befell her clinic, in the form of a patient who is also an electrical contractor.

“He said, ‘Hey, I’ve got coveralls and goggles. Do you want them?’” she said. “So we’ve had some patients outreaching to see if they can be helpful.”