COLUMBIA, S.C. (AP) — Fifty-four years after they were sentenced to a month of hard labor in a chain gang for ordering lunch in South Carolina, nine black men are getting a new day in court.

A prosecutor was expected to ask a judge Wednesday to vacate the convictions of the men known as the Friendship Nine, who were arrested for integrating a whites-only lunch counter in the segregated town of Rock Hill.

The fact that these civil rights era crimes will no longer be on their records has brought mixed feelings to the men. Their refusal to pay bail money into the segregationist town’s city coffers served as a catalyst for other civil disobedience. Inspired by their courage, demonstrators across the South adopted their “jail not bail” tactic and filled jail cells. The media attention helped turn scattered protests into a nationwide movement.

“Everything that happened, happened for a reason,” W.T. “Dub” Massey, one of the nine, told The Associated Press. “We have to continue what we’re doing. If we’re backing off from what we’ve done, then there’s a problem here.”

Massey and seven other students at Rock Hill’s Friendship Junior College — Willie McCleod, Robert McCullough, Clarence Graham, James Wells, David Williamson Jr., John Gaines and Mack Workman — were encouraged to violate the town’s Jim Crow laws by Thomas Gaither, who came to town as an activist with the Congress of Racial Equality.

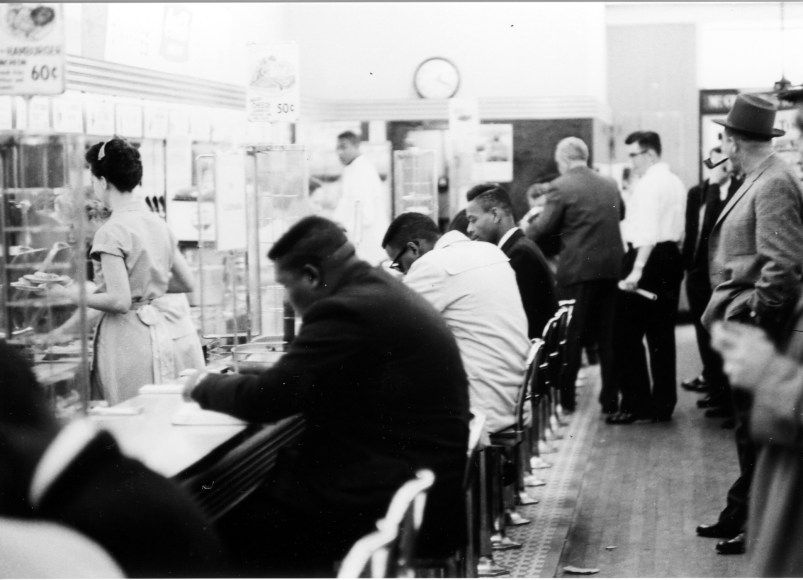

About a year had passed since a sit-in at a segregated lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina, helped galvanize the nation’s civil rights movement. But change was slow to come to Rock Hill. They decided to challenge matters by getting arrested in February 1961 for ordering lunch at McCrory’s variety store, and were convicted of trespassing and breach of peace.

Author Kim Johnson, who published “No Fear For Freedom: The Story of the Friendship 9” last year, went to Kevin Brackett, the solicitor for York and Union counties, to see what could be done to clean their records.

“This is an opportunity for us to bring the community together,” Johnson told the AP. “To have the records vacated essentially says that it should have never happened in the first place.”

Brackett’s request to a Rock Hill judge comes too late for McCullough, who died in 2006. But some of the others returned to town ahead of the hearing to reflect on their experience, saying they hope their actions can still have an effect.

“It’s been a long wait,” Graham said. “We are sure now that we made the right decision for the right reason. Being nonviolent was the best thing that we could have done.”

The men’s names are engraved on the stools at the counter of the restaurant on Main Street, now called the Old Town Bistro. A plaque outside marks the spot where they were arrested. And official and personal apologies have been offered to the men over the years.

In 2009, a white man named Elwin Wilson who tried to pull one of the protesters from a stool nearly 50 years earlier returned to the same counter, meeting with some of the men. They forgave him.

And although their records will soon be clean, the men hope their commitment to nonviolence can remain an example for people protesting various issues today.

“Maybe it might change some of their minds about some of their actions,” Graham said. “Until the hearts change, there won’t be any changes. We still insist that nonviolence is the way to go.”

___

Kinnard can be reached at http://twitter.com/MegKinnardAP .

Copyright 2015 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.