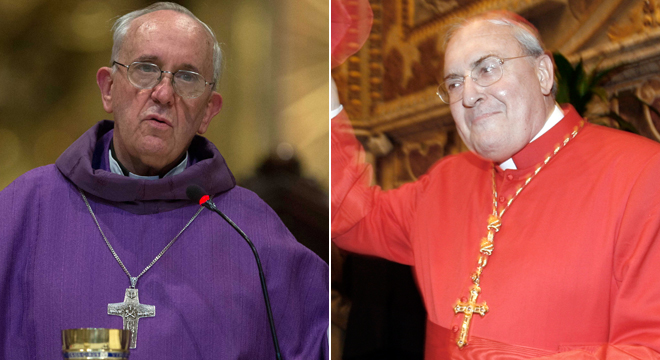

BUENOS AIRES, Argentina (AP) — Both are the sons of Italian immigrants. Both are doctrinal conservatives. And both are known for their warm personalities.

But the two Argentine cardinals widely given an outside chance to become pope have had very different careers.

Jorge Mario Bergoglio, who would be the first Jesuit pope if chosen, has spent nearly his entire career at home in Argentina, overseeing churches and shoe-leather priests. Leonardo Sandri, who left for Rome 42 years ago, is a Vatican insider who has run the day-to-day operations of the global church’s vast bureaucracy and roamed the world as a papal diplomat.

The election of either of them as pope might help to reconcile two conflicting trends in the papal election: the push to return to the tradition of Italian popes, and the longing for a pontiff from the developing world.

___

EDITOR’S NOTE: As the Roman Catholic Church prepares to elect a successor to Pope Benedict XVI, The Associated Press is profiling key cardinals seen as “papabili” — contenders to the throne. In the secretive world of the Vatican, there is no way to know who is in the running, and history has yielded plenty of surprises. But these are the names that have come up time and again in speculation. Today: Jorge Mario Bergoglio and Leonardo Sandri.

___

Bergoglio, 76, reportedly got the second-most votes after Joseph Ratzinger in the 2005 papal election, and he has long specialized in the kind of pastoral work that some say is an essential skill for the next pope. In a lifetime of teaching and leading priests in Latin America, which has the largest share of the world’s Catholics, Bergoglio has shown a keen political sensibility as well as the kind of self-effacing humility that fellow cardinals value highly, says his official biographer, Sergio Rubin.

Bergoglio would likely encourage the church’s 400,000 priests to hit the streets to capture more souls, Rubin said in an Associated Press interview. He is also most comfortable taking a low profile, and his personal style is the antithesis of Vatican splendor. “It’s a very curious thing: When bishops meet, he always wants to sit in the back rows. This sense of humility is very well seen in Rome,” Rubin said.

Bergoglio is known for modernizing an Argentine church that had been among the most conservative in Latin America,

Sandri, 69, left for Rome at 27 and never came back to stay in Argentina. Initially trained as a canon lawyer, he reached the No. 3 spot in the church’s hierarchy under Pope John Paul II, the zenith of a long career in the Vatican’s diplomatic service ranging from Africa to Mexico to Washington.

As substitute secretary of state for seven years, he essentially served as the pope’s chief of staff, running the central office at the heart of the Vatican bureaucracy known as the Curia.

“It’s hard to find somebody in church circles who doesn’t like Sandri. Granted, few might describe him as ‘charismatic,’ but he’s almost universally seen as warm, open and possessing a lively sense of humor,” Vatican analyst John Allen wrote in the National Catholic Reporter. “Personal relationships are all-important, and Sandri has a lot of friends.”

The jovial diplomat has been knighted in a dozen countries, and the church he is attached to as cardinal is Rome’s gorgeous, baroque San Carlo ai Catinari. In contrast, Bergoglio stands out for his austerity. As Argentina’s top church official, he’s never lived in the ornate church mansion in Buenos Aires, preferring a simple bed in a downtown room heated by a small stove on frigid weekends. For years, he took public transportation around the city, and cooked his own meals.

Bergoglio has slowed a bit with age and is feeling the effects of having a lung removed due to infection when he was a teenager — two strikes against him at a time when many Vatican-watchers say the next pope should be relatively young and strong. “But he’s going to be very influential in the congress of cardinals, one of those who is most listened to,” Rubin said.

Sandri, on the other hand, seems robust. He’s also relatively unscathed by recent Vatican controversies.

It was seen by some as a demotion when Benedict replaced Sandri as his No. 3 in 2007, putting him in charge of Eastern-rite churches, a job outside the pope’s inner circle. But Sandri left with a reputation for no-nonsense, efficient governance, and was out of the way when a scandal over leaked documents and other controversies vexed the papacy, Allen said.

Sandri remains a consummate Vatican insider. Benedict promoted him to cardinal and named him to the Vatican’s Supreme Tribunal, which provides the second-to-last word on church law, after the pope. Sandri also is one of very few cardinals in the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, the rule-making bastion Ratzinger led for many years before becoming pope.

The Catholic faithful probably best remember him as the “voice of the pope” who delivered papal speeches when John Paul II became too infirm, and it was Sandri who announced the beloved pope’s death to the crowd in St. Peter’s Square, adding the memorable observation that “we all feel like orphans this evening.”

But Sandri has never led a congregation, a strike against him for cardinals who want the next pope to have pastoral experience, Allen said.

Both men are seen as moderates with open minds, even as their doctrinal and spiritual positions remain well in line with the legacy of John Paul II and Benedict XVI, both conservative popes.

Bergoglio couldn’t prevent Argentina from becoming the first Latin American country to legalize gay marriage, or stop its president, Cristina Fernandez, from promoting free contraception and artificial insemination. When Bergoglio argued that gay adoptions discriminate against children, Fernandez compared his tone to “medieval times and the Inquisition.”

This kind of demonization is unfair, says Rubin, who wrote Bergoglio’s authorized biography, “The Jesuit.”

“Is Bergoglio a progressive — a liberation theologist even? No. He’s no third-world priest. Does he criticize the International Monetary Fund, and neoliberalism? Yes. Does he spend a great deal of time in the slums? Yes,” Rubin said.

Critics also accuse him of failing to stand up publicly against the country’s military dictatorship from 1976-1983, when victims and their relatives often brought first-hand accounts of torture, death and kidnappings to the priests he supervised as leader of the Jesuit Order in Argentina

Like other Jesuit intellectuals, Bergoglio has focused on social outreach. Catholics are still buzzing over his speech last year accusing fellow church officials of hypocrisy for forgetting that Jesus Christ bathed lepers and ate with prostitutes.

“In our ecclesiastical region there are priests who don’t baptize the children of single mothers because they weren’t conceived in the sanctity of marriage,” Bergoglio told his priests. “These are today’s hypocrites. Those who clericalize the Church. Those who separate the people of God from salvation. And this poor girl who, rather than returning the child to sender, had the courage to carry it into the world, must wander from parish to parish so that it’s baptized!”

Bergoglio compared this concept of Catholicism to the Pharisees of Christ’s time: people who congratulate themselves while condemning others.

“Jesus teaches us another way: Go out. Go out and share your testimony, go out and interact with your brothers, go out and share, go out and ask. Become the Word in body as well as spirit,” Bergoglio said.

Copyright 2013 The Associated Press.