President Trump’s inaugural committee failed to disclose to the IRS how much money it received in ticket revenue, TPM has found after reviewing the group’s tax filings, a failure that tax experts find perplexing.

The Trump inaugural committee’s failure to identify the revenue it generated from the sale of tickets and other perks broke with the practice of previous inaugural committees. In doing so, the tax return that the committee filed with the IRS obscured a key metric of how it raised its record $106.7 million.

On their tax returns, other recent inaugural committees broke out sales revenue separately from contributions from donors. Sales of tickets to events, which often include key officials from the incoming administration, and of merchandise or other items of value were typically listed on the inaugural committee’s tax return where it asks for “program service revenue.”

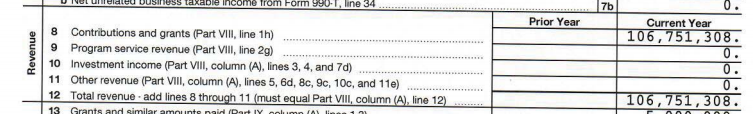

The Trump inaugural committee did not report any “program service revenue” on its tax return, effectively concealing the amount of cash generated from tickets and anything else that it sold.

“I can’t think of a legitimate reason why one would not do that,” Marcus Owens, an attorney at Loeb & Loeb who served as director of the IRS’s exempt organizations division for 10 years, told TPM. “Confusion by the accountant perhaps. Obviously, the form calls for it, so the form is not complete and accurate if doesn’t do that.”

In a statement to TPM, the inaugural committee asserted that it had complied with all relevant regulations.

“Only one inaugural event had publicly available paid tickets, which was the Inaugural Ball at $50 per ticket,” committee spokeswoman Kristin Celauro said. “Many guests to this ball also received tickets free of charge or as part of donor packages.”

Owens laughed after TPM read him the inaugural committee’s response.

“That’s just incorrect,” he scoffed. “If you pay for a package and it includes your tickets, hotel room, transportation, a free bottle of champagne, funny hats — those are all fees for goods and are not contributions.”

The Wall Street Journal released a story in December saying that Manhattan federal prosecutors opened a criminal probe into the inauguration’s spending and into whether some of the committee’s top donors had traded cash for access to the Trump administration. The missing data on the tax return could reveal whether lavish donation packages factored in to the inauguration’s record-high price tag.

Breaking With The Past

By all accounts, Trump wanted his inaugural bash to be yuge.

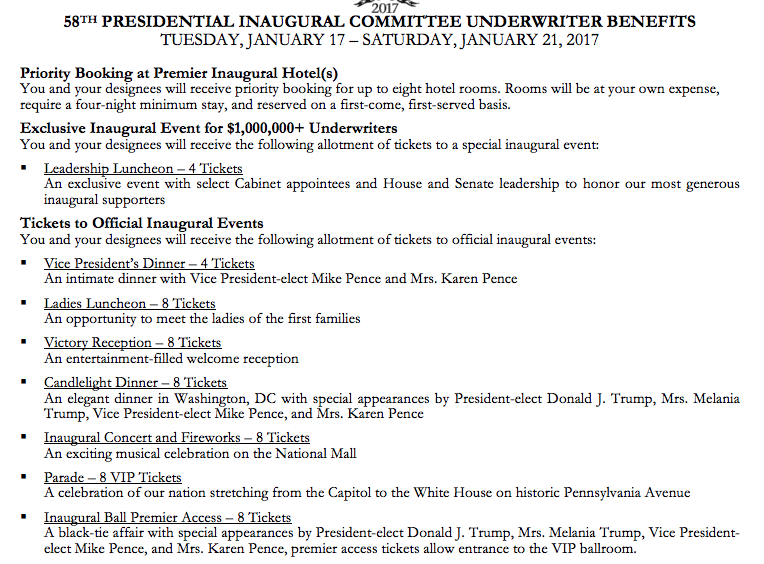

A November 2016 “underwriter response form” listing different contribution packages shows what potential donors could receive in exchange for forking over cash to the committee. The most extravagant options — available to donors giving more than $1,000,000 — included transportation, hospitality, hotel bookings, and tickets to seven different events — not including the inauguration ceremony itself.

A Boston Globe report at the time said that many top Republican donors who didn’t believe Trump could win saw lavish contributions to the inaugural as a means to “find a way in” to the administration.

But it’s not clear how much the donors got in return, in the form of tickets, transportation expenses, or other things of value. On the inaugural committee’s tax return, that information should be logged under “program service revenue,” tax attorneys told TPM. Instead, it’s listed as “0”:

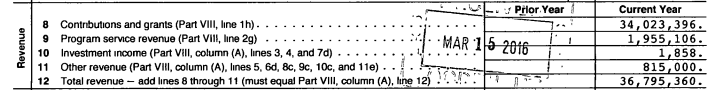

In 2013, the inaugural committee for Obama’s second term logged nearly $2 million in that form of revenue on its 990 filing:

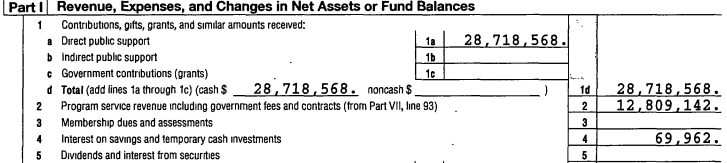

The 2005 Bush inaugural recorded more than $12 million in “program service revenue,” possibly reflecting the whopping 50 balls held around Washington, D.C., at the time for delegations from each state:

Differences in program service revenue between inaugurations are at least partly accounted for by what was provided to donors. An inaugural committee that offered limo rides and luxury hotel stays would have a higher number, for example.

For the Trump inaugural in particular, the failure to delineate different forms of revenue obscures a key part of how it managed to raise its record $106.7 million, a number that dwarfs all previous inaugurals by at least $50 million. It also hides the value of what was given to top donors in exchange for their cash.

It’s difficult to overstate how much more money was raised – and spent – on the Trump inaugural compared to previous recent inaugurals, especially considering the relatively modest size of Trump’s festivities, which was in part a reflection of his surprise victory and the sudden scramble to plan an inauguration. Obama’s first inaugural committee took in $55 million in revenue. Bush’s 2005 inaugural brought in revenue of $41.9 million ($54 million when adjusted for inflation as of 2016).

“It would be like our inaugural raising $54 million, spending it on staff and events, and then raising the money all over again and finding a way to distribute it after all the bills have been paid,” said Greg Jenkins, who ran Bush’s 2005 inaugural. “That’s what’s baffling to me, they could have raised less than what we did.”

Belle Of The Ball

The Trump inaugural committee told TPM that it only sold tickets to one combined event, the Liberty Ball and the Freedom Ball at the DC convention center. The rest of the events were free, the committee said, obviating the need to disclose sales-based revenue for them.

“The inaugural ball was the only public event during the entirety of the inauguration where there was a cost of admission,” Celauro, the inaugural committee spokeswoman, told TPM. “All other public events, such as the swearing-in ceremony, parade and the welcome concert, were free of charge.”

Forms provided to donors show, however, that tickets were required to access other portions of the inauguration.

“If you needed a ticket to get in, then it’s not a contribution — it’s an admittance fee,” Owens, the former IRS attorney, said.

Jenkins, the Bush 2005 inauguration chief, called it a “head-scratcher.”

“Obviously, they did sell tickets,” he added.

After initially reviewing a list of TPM’s questions, a representative of the inaugural committee agreed to give TPM the amount of revenue generated from ticket sales. One day later, the representative reneged, declining to provide the delineated amount.

Malfeasance Or Ineptitude?

Though the Mueller investigation remains a black box of information apart from its public filings, there are suggestions that investigations into the inaugural are heating up.

CNN, the New York Times, and the Wall Street Journal have reported that prosecutors are investigating whether foreigners were able to buy “influence over American policy” at the event, and whether money was misallocated.

Inaugural committee chair and Trump confidant Thomas J. Barrack, Jr. issued a statement in response saying that he was not under investigation. Former Manafort deputy and current Mueller witness Rick Gates was deputy chair of the inaugural, while Elliott Broidy — under investigation in his own foreign influence peddling scandal — was a finance co-chair.

Prosecutors from the special counsel’s office attended a recent court hearing for W. Sam Patten, a D.C. lobbyist who admitted to taking $50,000 from a Ukrainian politician to buy four tickets to the inaugural, directing the money through a straw purchaser to the inaugural committee. That admission came as part of an August guilty plea in D.C. federal court over failure to register as a foreign agent, in a case brought by the U.S. attorney’s office, not Mueller.

House intel committee chair Adam Schiff (D-CA) is probing the issue, telling TPM in a statement that “allegations concerning the inauguration and its funding surfaced early in the investigation and remain a matter of interest and concern to the Committee.”

“Whenever a foreign nation uses its financial wealth to violate the laws of our country, it undermines our democracy,” Schiff added. “When another country does so in concert with U.S. persons, it carries the additional risk of compromising them and presents a particularly acute counterintelligence risk.”

The reporting requirements on the inaugural committee’s tax return are different from those of the FEC, according to former FEC General Counsel Larry Noble. The committee reported a total of $106.7 million in receipts to the FEC, the same it reported to the IRS.

Part of the issue goes to how the value of tickets are calculated by non-profits. Typically, the full value of the ticket “is considered a contribution” for the purposes of the FEC, Noble said.

For IRS purposes, the requirements change. The base market value of the ticket is meant to be reported on the tax return, Noble said, while “the amount above the fair market price is a contribution.”

“But any donations made and ticket sales should be included in the FEC form as well,” Noble added.

It remains unclear why the ticket sale revenue is not separated on the tax return, or what exactly that might conceal.

“That’s an important distinction because donations represent things people did for free as gifts, while ticket sales were given in return for something,” Peter Swords, a former president of the Nonprofit Coordinating Committee of New York, told TPM.

Swords added that it was unclear if the issue boiled down to incompetence or malfeasance.

“At best, it’s sloppy reporting, and at worst, may be hiding some transgression,” he said.