Members of the Aryan Brotherhood of Texas prison gang like tattoos. Nazi flags, swastikas, iron eagles, and Schutzstaffel “SS” lightening bolts are popular. But one design in particular, called the Aryan Brotherhood of Texas patch, according to federal court documents, is of particular significance. The patch’s shape and design can vary, but it usually includes a shield, a sword, a swastika, and a crown, with the letters “A” and “B” along with the Nazi “SS” above the shield and the word “Texas” below. The patch can only be worn by “fully made” members of the gang, who generally ascend to that status by committing a “blood-tie” on behalf of the gang. In other words: aggravated assault or murder.

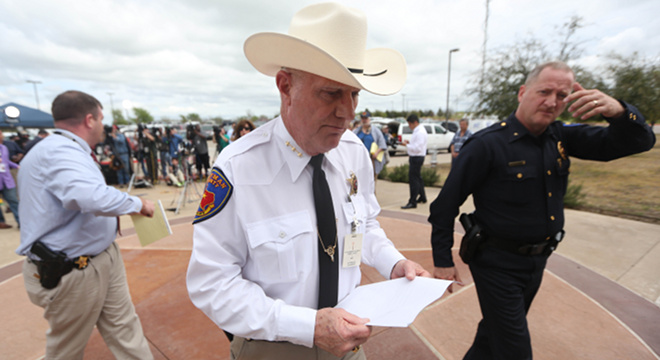

The recent killings of two prosecutors in Kaufman County, Texas has resulted in a spate of media reports about the Aryan Brotherhood of Texas, which the Anti-Defamation League last year called the “most vioÂlent extremÂist group in the United States.” While no material evidence has been found linking the gang to the murders, the Kaufman County District Attorney’s Office was part of a multi-agency task force that worked on a large racketeering case targeting the group. And law enforcement officials investigating the killing have been conducting interviews with members of the gang.

The first Kaufman prosecutor killed, Assistant District Attorney Mark Hasse, was shot dead outside the county courthouse on Jan. 31, the same day the Justice Department announced that two members of the gang had pleaded guilty in the case. On Saturday, law enforcement officials found the bodies of District Attorney Mike McLelland and his wife, Cynthia McLelland, inside their Forney, Texas home. Both had been shot. Three days after the McLellands’ bodies were found, a federal prosecutor withdrew from the racketeering case, citing security concerns in an email to defense attorneys.

No suspects have been publicly named in the prosecutor murders, and investigators are still following several leads, but even Texas Gov. Rick Perry (R) has addressed the reports of the Aryan Brotherhood of Texas connection.

“I think it is obviously … too early to be speculating whether there is any direct contact,” Perry told Fox News on Wednesday, after being asked to comment on reports connecting the Aryan Brotherhood of Texas to the killings. “But again, I think it is wise for us to not overlook any evidence that either may be superficial or otherwise. So they are here. They are active in this state.”

Set up in the early 1980s, the Aryan Brotherhood of Texas was started by a group of white inmates in Texas prisons. Separate from the Aryan Brotherhood, an older and larger white supremacist prison gang formed in California in the late 1960s, the first members of the Aryan Brotherhood of Texas actually asked the older group for permission to start a Texas chapter. Their request was denied, but they formed their own group anyway, and borrowed the name and many of the older group’s precepts. Like the original Aryan Brotherhood, the Aryan Brotherhood of Texas maitains a military structure — members hold ranks like general, major, lieutenant, etc. — and uses of sophisticated system of written and verbal codes. The gang’s various rules, procedures, and code of conduct are laid out in a written constitution, which is distributed to members. In Texas, according to federal court documents, there are actually two competing Aryan Brotherhood of Texas factions.

The government has accused members of the group of a range of serious criminal activities, including murder, attempted murder, kidnapping, assault, narcotics distribution, weapons trafficking, arson, and counterfeiting. Since its formation, the Aryan Brotherhood of Texas members have been responsible for more than 100 murders and at least 10 kidnapping, according to Mark Potok, a senior fellow at The Southern Poverty Law Center, which tracks hate groups.

“These gangs are increasingly spilling out of the prisons and into our communities,” Potok told TPM in an interview this week. “The American public, which by and large has been pretty much unaware of these groups, is facing them for the first time.”

Potok cited two reasons for the gangs’ increasing presence outside prisons. For one thing, as the gangs get older, more members who had been serving long sentences are getting out. And the gangs are also increasingly demanding that people stay in the organization after they leave prison.

“It used to be — not so long ago, 10 years ago — it used to be very typical, you might join a white supremacist gang when you go in simply as a matter of self-protection,” Potok said. “But very often that membership was simply dropped when you walked out of prison on your release day. That’s much less true now.”

Like other white supremacist prison gangs, the Aryan Brotherhood of Texas’ racist ideology takes a backseat to its everyday criminal activities. According to the Anti-Defamation League, the gang’s constitution acknowledges that it can be a “hindrance” to put ideÂoÂlogÂiÂcal beliefs before “busiÂness transÂacÂtions.” Last year, the ADL looked at the 29 known murders committed by Aryan Brotherhood of Texas members and associates between 2000 and 2012. Only three of the murders were found to have been hate-related.

“[M]any ABT murÂders take place in conÂnecÂtion with their ‘traÂdiÂtional’ crimÂiÂnal activÂiÂties, such as methamÂphetÂaÂmine trafÂfickÂing, home invaÂsions, and idenÂtity theft,” the ADL said in a blog post. “Even more ABT murÂders are actuÂally interÂnal murÂders”

On Tuesday, TPM spoke with Katherine Scardino, a Houston attorney representing one of the defendants in the federal racketeering case. Scardino’s client, Terry Sillers, was a “general” in the Aryan Brotherhood of Texas. Sillers has agreed to cooperate with the government and pleaded guilty in the case. He is currently under protective custody, and not even his lawyer knows where he is being held.

“I don’t know where Mr. Sillers is,” Scardino told TPM. “And I don’t really want to know.”