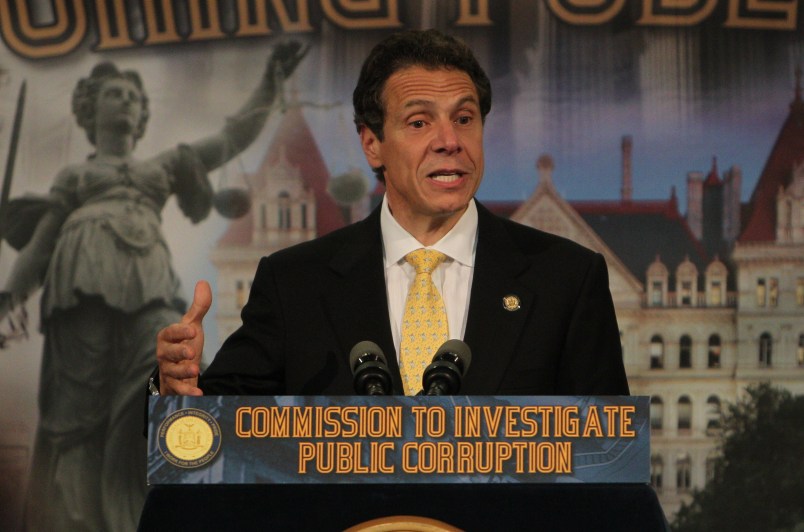

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo (D) and his office stymied investigations into political allies and associates being undertaken by an independent commission that Cuomo created to stop public corruption, the New York Times reported on Wednesday after a three-month investigation by the newspaper.

The most obvious interference, according to the Times, came when the commission sent a subpoena to Buying Time, a media company through which Cuomo had spent $20 million on ads since 2002. The commission was looking into the company’s relationship with the New York Democratic Party, and it did not know of the firm’s ties to Cuomo when it issued the subpoena.

A top Cuomo aide, Lawrence Schwartz, quickly scuttled the order. “This is wrong,” he told a commission chairman, according to the Times. “Pull it back.”

The episode was, according to the newspaper’s investigation, part of a broader pattern of behavior by the governor’s office. Cuomo disbanded the commission a full eight months before it was supposed to finish its work, claiming a legislative reform package that many criticized as watered down was the culmination of its duties.

In a 13-page statement to the Times, Cuomo’s office dismissed the premise of the newspaper’s investigation as “legally, ethically and practically false.”

“Your fundamental assertion is that the Commission was independent. It wasn’t,” the office wrote. The statement also said that many of the companies for which Cuomo’s staff had reportedly interfered did eventually receive subpoenas. That included Buying Time, according to the Times.

The Times investigation lands as Cuomo is running for re-election and faces a federal inquiry into his decision to shutter the commission. For their part, some who worked with commission viewed its work, which Cuomo highlighted in re-election ads, as an obviously political exercise.

“The thing that bothered me the most is we were created with all this fanfare and the governor was going to clean up Albany,” Barbara Bartoletti, the legislative director for the League of Women Voters of New York State and an adviser to the commission, told the Times. “And it became purely a vehicle for the governor to get legislation. Another notch for his re-election campaign. That was it.”

Cuomo established the commission, granting it significant autonomy and subpoena power, in July 2013 after a string of scandals shook the New York capitol. He said it would have until the end of 2014 to uncover and expose public corruption.

“The people of this state should sleep better tonight,” he said at the time, according to the Times. It was chaired by two district attorneys, one of whom was a Republican, and a former federal prosecutor. The executive director was Regina Calcaterra, a former securities lawyers who routinely communicated with Schwartz during the commission’s work. Top attorneys and professors filled out the 25 seats on the commission.

They had the expected purview of an ethics task force: campaign donations, outside employment by state officials and expense reimbursements known as “per diem” payments, which are notoriously easy to abuse. They even had the permission, at the start, anyway, to investigate the governor’s own fundraising, one of the chairs said at the time, per the Times.

Schwartz later clarified that Cuomo himself was not to be touched, according to the Times, though the commission evidently never looked into him anyway.

The Times, often citing anonymous sources familiar with communications between Cuomo’s office and the commission, detailed a number of instances when the governor’s staff intervened.

In one instance, a subpoena for the Real Estate Board of New York, which has donated money to Cuomo. Schwartz called the commission’s chairs “in a fury” and instructed that the subpoena would not be issued, according to the Times.

In another, a subpoena was readied for a major retailer, not identified by the Times, to see if its campaign donations coincided with a tax credit that had been passed. Calcaterra told E. Danya Perry, a former federal prosecutor and the commission’s top investigator, that the inquiry could reflect poorly on Cuomo because he included the tax credit in his own budget.

The governor’s office also selected the person who would author the commission’s initial report, according to the Times, and Calcaterra deleted references in the report to groups friendly to Cuomo.

The commission was shut down on March 29 with, the Times noted, much less ceremony then it had been created. Cuomo had to be asked by a reporter about the commission’s status, according to the Times. The governor replied that it had achieved its objectives.