The Environmental Protection Agency has granted almost $3 million to researchers to simulate the functions of a human liver in an effort to replace the expensive and cruel process of testing the impact of environmental toxins on rodents.

The computer liver is part of EPA’s virtual organ program — several other government agencies are working on similar projects.

The Food and Drug Administration is also working on computer simulations of the liver to test the safety of new drugs.

The liver functions as the body’s sewage treatment plant. It filters the blood and produces proteins for digestion. It is a forgiving organ, capable of rebuilding itself after damage.

Sometimes, however, it gets overwhelmed or meets a toxin it can’t handle, making a person sick. Sometimes a medicine will have an unintended–perhaps fatal–side-effect on a patient and the first damage is often in the liver.

What medical scientists now call the “gold standard,” the test that gives the best results in a study, involves testing compounds on animals, usually rats and mice, occasionally dogs.

They are subjected to the chemicals, “sacrificed” and they and their livers are inspected to check for damage.

Besides killing many rodents, animal testing has its problems. First, mice and rats aren’t people and what happens to them does not always translate into what happens to humans.

Also, the lab animals are bred to be identical, but except for identical twins, humans aren’t, so different people can react differently to different substances..

Additionally, said Paul Watkins of the Hamner Institute, one of the laboratories involved in the work, the maximum safe dose allowed for humans often is the dose that makes laboratory animals sick. Humans sometimes could tolerate larger doses but there is no safe way to know that.

The simulated liver would also help the EPA deal with a larger volume of tests more quickly: The agency would like to use the software to test as many as 10,000 chemicals. With animal tests, each test could take years.

“Our goal,” said Watkins of his project, is “not to kill animals any more.”

Watkins is working with the University of North Carolina at Chapel Institute for Drug Safety Sciences on the project called Drug Induced Liver Injury simulation model (DILI-sim).

Down the street at Research Triangle Parkt, the EPA has contracted with four groups to develop the vLiver at the EPA’s National Center for Computational Toxicology.

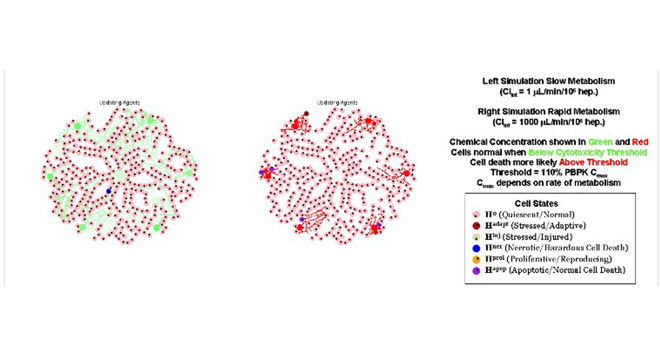

Technically, what they are working on is not a virtual liver: The results are not graphic pictures of the liver, something you might develop to teach medical students, but a series of numbers on a printout or on the screen. They are mathematical representations of the liver.

DILI-sim and vLiver have different goals and take different techniques.

The EPA model works from the bottom up, looking at the effects of a pollutant on the cells in the liver. It concentrates on the cellular level and then tries to predict what happens to those cells when a drug is introduced. It looks for physical and genetic changes in the cell, and what happens to them with their surroundings. For instance, does it change how the cells communicate with each other?

UNC’s DILI-sim does the reverse: it takes tests already done with animals and is developing a computer model that would produce the same results without the animals. The researchers already know the effects of the drugs they are testing and want to build a system that would produce the same results to prove it works. Then they can move on to testing new drugs, Watkins said.

Most of the projects began less than a year ago and it will be years before they are commonly used.

Joel N. Shurkin is an author and freelance writer in Baltimore, MD. He is the author of nine books, which include: Invisible Fire, The Eradication of Smallpox; Engines Of The Mind, A History Of The Computer; Terman’s Kids, The Groundbreaking Study Of How The Gifted Grow Up; and Broken Genius, The Rise And Fall of William Shockley.

Have a story idea or tip for Idea Lab? Send them to: idealab@talkingpointsmemo.com