Rooftop fuel cells may one day join refrigerators, furnaces, and yes, chicken dinners among the staples of modern domestic life in the U.S.

That could be the outcome of a new solar-fuel cell hybrid system under development by Duke University researcher Nico Hotz, who foresees that fuel cells may eventually trump rooftop solar panels as the equipment of choice for building owners who want to generate their own clean, cheap, renewable energy.

In contrast to traditional means for creating energy by burning fuels like coal and oil, fuel cells create energy by chemical reaction.

Until now, hydrogen has been the standard ingredient for fuel cells, but hydrogen production involves expensive processes all the way through from production to storage. That’s one reason why fuel cells have been slow to make inroads into the alternative fuel vehicle market, let alone development for household use.

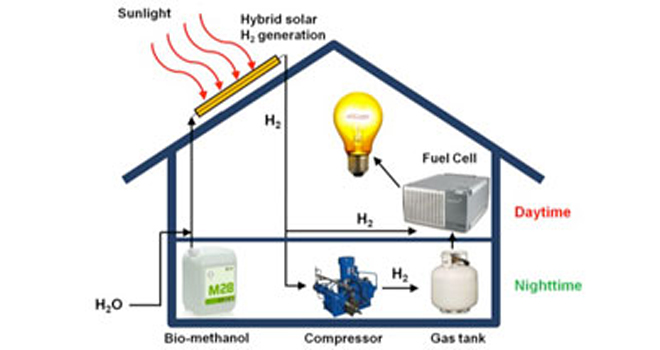

Hotz is designing a low cost fuel cell system that would enable building owners to collect solar energy from a system of tubes placed on a rooftop. The tubes would contain a mixture of water and methanol, and the sun would generate enough heat to produce the two reactions needed to produce hydrogen from the mix.

As for why a building owner would choose to produce hydrogen rather than simply install solar panels, the advantage is in energy storage. When combined with a fuel cell, Hotz’s solar energy system would keep humming along, producing power regardless of whether or not the sun is shining.

The concept of home-based, large scale energy storage shouldn’t sound too far-fetched to homeowners who have oil tanks in stationed their basements or buried in their grounds, or for people who put away a shed full of firewood for the winter. The solar-fuel cell hybrid system simply adds new high tech twist to an old idea.

Hotz’s system is based on a matrix of vacuum-sealed copper tubes coated with a thin layer of aluminum and aluminum oxide. For heating a liquid, this arrangement is much more efficient that conventional solar panels.

“The set-up allows up to 95 percent of the sunlight to be absorbed with very little being lost as heat to the surroundings,” Hotz explained in a recent article from Duke University. “This is crucial because it permits us to achieve temperatures of well over 200 degrees Celsius within the tubes.”

In contrast, according to Hotz a typical solar collector can only heat water up to 70 degrees Celsius.

Hotz is not the only researcher to explore the potential for solar powered fuel cells to provide low cost, clean, renewable energy for individual buildings.

At MIT, Daniel Nocera is leading a research team that is developing an electronic silicon-based “artificial leaf” about the size of a playing card. When dipped in a gallon jug of water exposed to bright sunlight, the device sets off a chemical reaction that produces hydrogen, and the hydrogen would be used to power a small fuel cell.

So far, Hotz’s design is yielding an installation cost of about $7,900, which is far more expensive than a conventional diesel generator. However, over the long run it could compete with fossil fuels on operating costs. As a large-scale system it could also provide building owners with income at least part of the year, when it could generate excess energy that would be sold back to the grid.

Nocera’s team is focused closely on a less expensive, smaller scale unit that could be affordable to households in developing countries as well as in the U.S.

“Our goal is to make each home its own power station,” said Nocera in a recent MIT article. “We’re working toward development of ‘personalized’ energy units.”