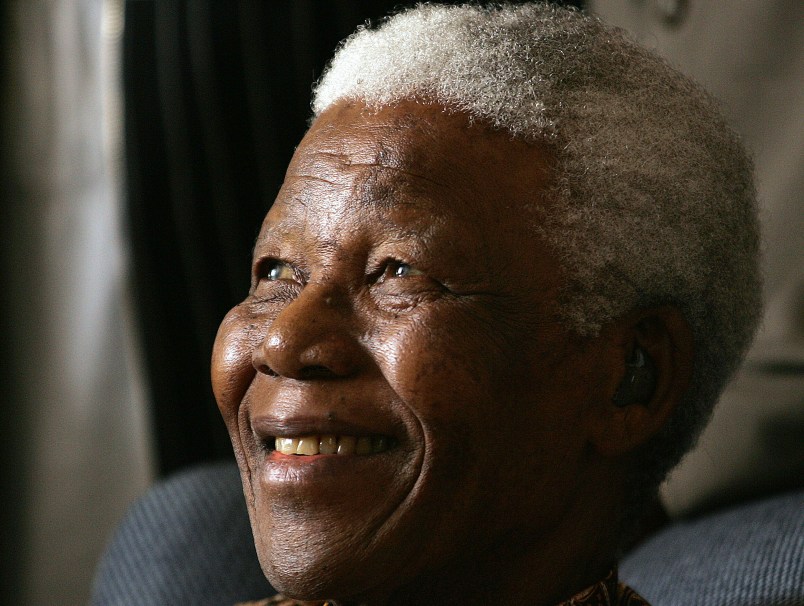

When someone of Nelson Mandela’s stature, historic significance and personal greatness dies, there’s really nothing to say for most of us that isn’t trite or unneeded. That seems especially so in this case in which Mandela’s passing has elements of a blessing in human terms, given his great age and deep enfeeblement and apparent suffering. But after a day of absorbing this expected news, there is one thing I would like to add: violence. And I mean that in a good way.

The iconic Mandela of today is the man who walked out of prison in 1990 focused not on retribution or black rule but majority rule, multiracial democracy. There’s the symbolically significant step at the center of the movie Invictus in which he embraced the Springboks, South Africa’s national rugby team which had been very much the team of white South Africa. Then later after his single term as President the seemingly ageless revered world statesman.

But that wasn’t the only Mandela. Mandela also embraced violence to end Apartheid or ‘the armed struggle’ to use the catchphrase of 20th century revolutionaries.

He didn’t come to it happily or quickly. His initial activism was of the ANC/Congress Party non-violent anti-colonial resistance variety. And he set it aside when a viable path to democracy appeared to open without it. It’s also true that not all violence is equal. Violent revolutionary movements tend include deeply moral people and sociopaths. But Mandela was a revolutionary. He wasn’t in prison because he was framed. He was in prison because he was an enemy of state and committed to its violent overthrow. (Here’s an interesting exploration of the role of anger and violence in Mandela’s world and life by Christopher Dickey.)

He also had longstanding relationships with a whole list of America’s rolling list of third world bad guys – Gaddafi, Arafat, Castro et al.

Mandela was no Gandhi. And that’s okay. No appreciation of the man is more than a cliche or an evasion without this part of his story. Indeed, his greatness is impossible to understand without it. Remember, through the Reagan administration Mandela was a confirmed enemy of the state in the United States. Not among the public perhaps (Congress eventually overrode Reagan’s vetoes) but definitely with the government itself.

It should also stop us short a bit in our standard take on who the bad guys and good guys are, whether the categories are really so fixed. Political violence is always a scourge. But it’s certainly not always wrong.