If you take one thing away from the de-escalating nuclear option fight in the Senate, it should be that there’s very little appetite among senators for doing away with the filibuster on the merits. In fact, if you thought that the fight reflected a growing sense among Democrats that the Senate’s anti-majoritarian rules have crippled the body, you weren’t paying enough attention.

What the outcome establishes is that there’s a limit to norm-breaking in the Senate, and that Harry Reid and the Democratic caucus will reluctantly and narrowly change the rules if those norms aren’t ultimately restored. But they’d really prefer to leave minority powers in tact if at all possible. And ironically, the whole fight underscores how much those limits have been stretched in just the last eight years, since the old GOP majority used the same threat to similar effect.

The 2005 nuclear option fight was about judicial nominations. Then as now, the idea was that the rules had to be changed because they were being abused. And in the end the same basic threat forced Democrats to confirm some judges they would have rather filibustered.

Now, I personally think Republicans should have changed the rules back then, and more broadly that the Senate should become a “majority cloture” institution sooner rather than later.

But think about what happens when a judge gets filibustered. Yes it’s a big affront to both the nominee and the president and a lot of people understandably get angry about it. But what happens next is that the president nominates a slightly less liberal or slightly less conservative alternative (or just someone with fewer enemies) and that person gets a lifetime opportunity to make law from the bench. The consequences of judicial filibusters for future policy are impossible counterfactuals, but probably amount to very little or nothing at all. Nevertheless, in 2005, judicial filibusters triggered a nuclear option fight.

Fast forward to today, and you’ll see that things have actually gotten worse. Set aside picayune arguments about whose nominees have faced more filibusters, or whose nominees have had to wait longer for confirmation. This fight wasn’t about life-long judges but rather term-limited executive branch nominees. More to the point, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and National Labor Relations Board need their nominees confirmed for their agencies to function properly — or at all. So in addition to the insult and annoyance and wasted time, the envelope in this case had actually been pushed off the table. The consequences of these filibusters for future policy would have been immediate and very concrete. Nullification by parliamentary process.

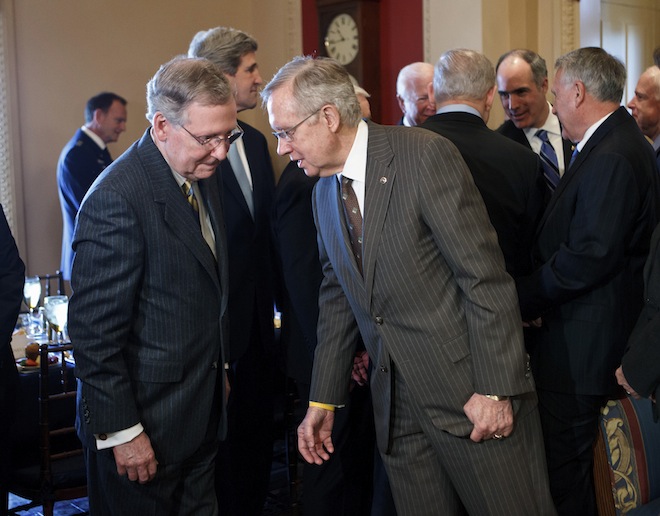

It obviously called for drastic action. Which is why I predicted back in early February — when Mitch McConnell renewed his CFPB filibuster threat — that getting Cordray confirmed would require reviving the filibuster reform fight, and result in either the nuclear option, or a cave.

Today the GOP caved. That’s a testament to Reid’s strategy and to the inherent power of the nuclear deterrent. But the fact that the threat itself is effectively a tool for reversing increasingly egregious acts of obstruction reflects very poorly on the Senate itself. And yet unless the something truly extraordinary happens, members are somehow OK with the way things work there.