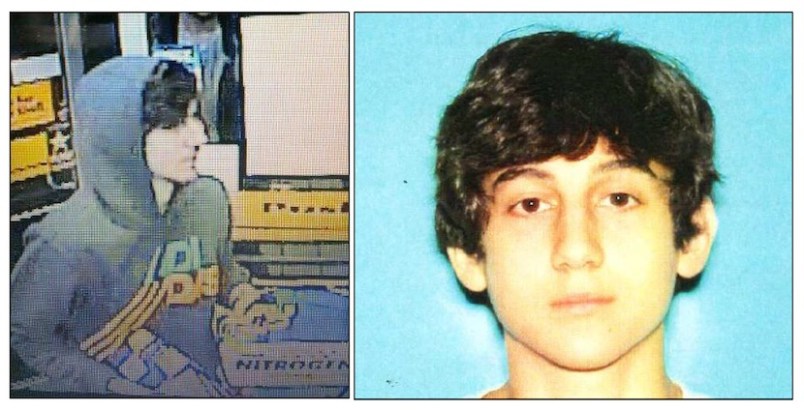

The Obama administration’s decision not to read Miranda rights to the Boston bombings suspect Dzhokhar Tsarnaev could be the first test of the relatively new expansion of the public safety exemption in terrorism cases.

The Justice Department informed the FBI, without approval from Congress or the courts, in October 2010 that it may interrogate a terrorism suspect without a Miranda warning on matters unrelated to an imminent threat if they believe the suspect may provide valuable intelligence. The Supreme Court has until now authorized the exemption only in cases involving an imminent threat to public safety.

Civil liberties advocates believe the Justice Department’s decision to invoke the public safety exemption for Tsarnaev could potentially lead to a legal challenge regarding the parameters of the exemption, with dangers to the prosecution of the suspected bomber.

“[I]f they try to use any of his pre-Miranda statements, it will almost certainly lead to a much-needed court ruling on the legality of the Obama DOJ’s interpretation,” Glenn Greenwald, a civil rights litigator and columnist for The Guardian, said in an email.

The American Civil Liberties Union said the public safety exemption is invalid in this case. “Every criminal defendant is entitled to be read Miranda rights,” said ACLU director Anthony Romero. “The public safety exception should be read narrowly. It applies only when there is a continued threat to public safety and is not an open-ended exception to the Miranda rule.”

The Supreme Court ruled in the landmark 1966 case Miranda v. Arizona that a suspect must be advised of the right to remain silent and to an attorney before any statements he makes may be admissible in court as evidence. The Court later carved out an exemption in the 1984 case New York v. Quarles for instances where there was believed to be an immediate threat that knowledge from the suspect could help defuse.

After 9/11, the Bush administration sought to end-run Miranda by declaring suspected terrorist José Padilla as an enemy combatant, thus stripping his rights. It held Padilla, a U.S. citizen, for three and a half years without charges or Miranda rights. He was later convicted by a federal court of terrorism conspiracy charges.

The Obama administration took a somewhat different approach and eventually sought to formalize a middle path for federal law enforcement to use in terrorism cases. The additional carveout for suspects in terrorism cases is not codified in law or established by the courts, but rather is internal Justice Department guidance. The Boston Marathon bombings case appears to be the first instance where DOJ’s guidance will be put into practice. As such, the exemption has not been previously reviewed by a court in a subsequent criminal trial, meaning the high-profile Boston case could be the first real test of its constitutionality.

On Dec. 25, 2009, Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, a Nigerian, attempted to detonate an explosive in his underwear during a flight from Amsterdam to Detroit. Authorities captured and questioned him for nearly an hour before reading him his Miranda rights, and said they had gained considerable information from the suspect. Abdulmutallab later tried to have his comments during that window thrown out in court, but failed, due to the public safety exemption. He was sentenced to life in prison.

In May 2010, Faisal Shahzad, a Pakistani-born naturalized American citizen, was arrested for attempting to detonate a bomb in Times Square. He was initially questioned without being read his Miranda rights, although authorities later said he cooperated with them before and after being informed of his rights. He pleaded guilty and was sentenced to life in prison.

That fall, the DOJ expanded that exemption on the heels of Republican criticism that the administration wasn’t being tough enough on terrorists — a move described by some experts as a middle ground between mirandizing suspects and stripping their rights by declaring them enemy combatants.

“There may be exceptional cases,” the DOJ memo read, “in which, although all relevant public safety questions have been asked, agents nonetheless conclude that continued unwarned interrogation is necessary to collect valuable and timely intelligence not related to any immediate threat, and that the government’s interest in obtaining this intelligence outweighs the disadvantages of proceeding with unwarned interrogation.”

Greenwald speculates that if the DOJ invokes its expanded exemption in this case, it could potentially jeopardize the prosecution of Tsarnaev “if the court rejects their interpretation and rules pre-Miranda statements inadmissible.”