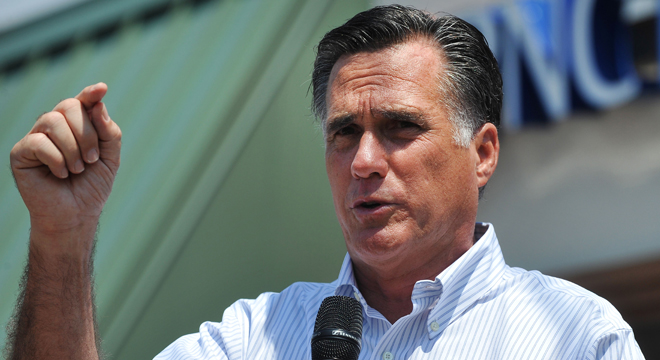

Mitt Romney appears to have been able to benefit in 2010 from tax rules that cut “active” investors a break on their losses, gains and expenses. It’s a perfectly legal deduction but one that shows how Romney and other high income Americans are subject to much different and more porous rules than most taxpayers.

As Huffington Post reports, Romney deducted hundreds of thousands of dollars in 2010 in expenses and interests related to partnerships — including Bain — to which he has financial ties. Those sorts of deductions are typically intended to apply to participants who are materially involved in their investments — and yet Romney publicly insists he took no part in Bain’s management decisions for the preceding 11 years.

In response to an inquiry from TPM, the Romney campaign said that this benefit has nothing to do with the candidates’ private sector activities in the last decade. “Whether an investor in a fund is entitled to an active deduction depends on whether the fund is active, not whether the investor is active,” a campaign official said on background. “Bain is active, so the deduction is active. The fact that Gov. Romney is a passive investor is irrelevant.”

Romney seems to have availed himself of an obscure regulation that allows even retired private equity and hedge fund executives like himself to reap the sorts of huge tax advantages intended for people who manage and operate the businesses they’ve put their own money behind.

“The short answer is the Treasury regulations that deal with passive activity losses have a special rule in them that the activity of trading personal property, which would include stocks that a partnership owns, should be treated as though it was an active, and not passive, activity,” says David Kautter, a tax expert at American University. “It is in fact a special rule that applies to a partnership that is actively trading stocks and bonds. They just automatically treat it as active.”

This particular loophole can in some cases turn lead into silver and silver into gold for wealthy, retired investors. When investments do well, gains are taxed at a low 15 percent top marginal rate. When they do poorly, the losses can be used to offset regular earnings, taxed at a much higher 35 percent marginal rate, and thus save the tax payer extraordinary sums of money.

According to Daniel Shaviro, a tax expert at New York University School of Law, that’s not really how things should work, and under other rules distinguishing between active and passive income, Romney likely wouldn’t have been able to avail himself of these benefits.

“[M]aterial participation has a bunch of different tests, but tends to require significant hours,” Shaviro emails. “[I]t’s hard to comment in the abstract. But it’s hard for me to see offhand how he could have gotten there post-2002.”

Assuming the carve out didn’t exist, the IRS says, Romney could have also reaped the active income benefit anyhow — if he demonstrated a managerial role in his investment partnerships in any five of the previous 10 years.

That would leave him in the unenviable position of explaining to voters why he claimed to have parted ways with Bain over a decade ago — but it’s an unlikely explanation, according to Kautter and Shaviro.

“[B]y 2010, it’s not clear how easily he gets to 5 years out of 10,” Shaviro notes.