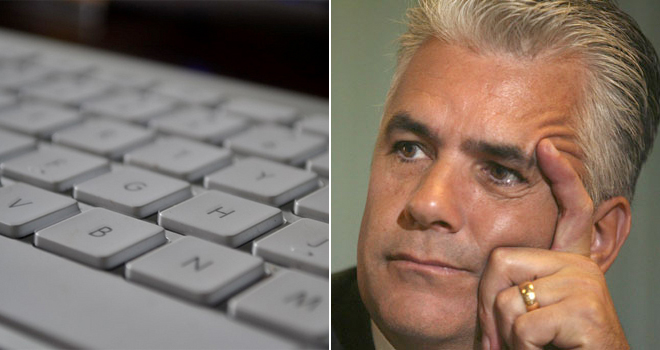

Former Sen. John Ensign’s (R-NV) legal fate may hinge on a gray area of the law governing the separation-of-powers between the legislative and judicial branches of government.

The Senate Ethics Committee’s decision to hand over all of its evidence in the case against Ensign to the Justice Department – which includes hundreds of e-mails as Reuters’ Murray Waas reported Thursday — has raised new questions about the Speech and Debate Clause of the Constitution and whether it can prevent DOJ prosecutors from using those e-mails and other documents obtained in the panel’s investigation that ended the Nevada Republican’s once promising political career.

After a nearly two-year Ethics Committee investigation into Ensign’s affair with his campaign treasurer, Cynthia Hampton, the wife of his closest friend and chief of staff, and his efforts to cover it up, a special prosecutor in the case found so much evidence of criminal wrongdoing she was prepared to recommend Ensign’s expulsion from the Senate.

Instead, Ensign resigned two days before his scheduled deposition before the panel and the Ethics Committee handed over a mountain of documents in the case to the Justice Department, which just months before had dropped its case against Ensign. The Speech and Debate clause, as well as attorney-client privilege protections, may have prevented the DOJ from gaining access to e-mails critical to the case. But the Senate Ethics Committee was not restricted by those same separation-of-powers issues.

But the law is anything but clear on the Justice Department’s use of evidence gained in a congressional ethics probe, and very few cases have dealt with the issue.

“There are so many brain twisters here because of how the evidence was developed by the committee during its own investigation – would that be privileged?” said Stan Brand, a longtime Washington ethics attorney to members of Congress accused of crimes.

The fact that the Senate Ethics Committee voluntarily handed the material over to Justice is another complicating wrinkle.

“You can’t ask them to prosecute then sit on your privilege,” he told TPM.

But the legal precedent in the matter is so slim that Ensign’s attorneys will no doubt try to argue the e-mails are protected.

The Speech and Debate Clause of the Constitution protects members of Congress from unwarranted intrusion from other branches of government on lawmaker’s official duties — but it doesn’t provide blanket protection over every action a member takes if it is personal or non-legislative in nature, and therein lies the rub.

Ensign created several personal e-mail accounts so those would likely have less protection than any relevant emails sent over his official Senate account.

“Anything set up on a [private] account would be a pretty far stretch under the Speech and Debate Clause,” argued Meredith McGehhe of the Campaign Legal Center.

There are also limits to the separation-of-powers protections — even over official, legislative activities.

“If there is treason, a felony or breach of the peace involved, than those protections are suspended” under the law, McGehee said.

Most political and legal observers remember the uproar over the FBI’s unprecedented raid on former Rep. William Jefferson’s (D-La) Capitol Hill office in 2006. Then Speaker Dennis Hastert (R-IL) and Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) stood together to denounce the raid, arguing that the FBI dangerously eroded the separation of powers between the two branches.

A judge ultimately ruled that prosecutors could not use the documents — including e-mails – seized during the raid in their case against him. Nevertheless, Jefferson lost his election and was eventually found guilty on multiple counts of corruption.

The case, however, showed just how time-consuming it is to weigh each individual document and e-mail against the Speech and Debate Clause protection. The Justice Department tried to argue in Jefferson that they would have a filter team, separate from the prosecutors, weigh each individual document and email. But a judge said that wasn’t good enough.

“The Jefferson case is going to be very instructive on the limits of the Justice Department’s ability to call those balls and strikes itself,” said Stefan Passatino, an ethics attorney at McKenna Long & Aldridge who is representing “staffer A” in the Ensign case.

The last time the courts ruled on the more narrow issue of whether Justice can use information gained in a Congressional ethics committee investigation was in July 2009. Then-Rep. Tom Feeney (R-FL), who was part of the government’s investigation of lobbyist Jack Abramoff, tried to prevent a grand jury from gaining access to statements he previously made to the ethics committee about an Abramoff sponsored golf trip to Scotland.

Feeney agreed to pay $5,643 to the Treasury for his trip after the House ethics committee scolded him for failing to find out who was really paying for it and whether there was any actual substance involved.

But even then the courts were extremely divided on the scope of protection his statements to the ethics committee should receive.

Then-Chief U.S. District Judge Thomas Hogan of D.C. had ruled for the Justice Department in May 2008 arguing that Feeney was acting in his personal capacity–and not his legislative one–when his attorneys provided statements to the House ethics committee.

But an appeals court unanimously reversed that ruling the following year. Judge Brett Kavanaugh, part of the three-judge panel that ruled in favor of Feeney, even called for an en banc hearing to clarify the protections accorded to evidence gathered during House and Senate ethics committee investigations.

With all of these complicated constitutional constraints, the case against Ensign may well be determined by just how hard the Justice Department is willing to fight. The department’s Public Integrity Section, which handles corruption and other cases against members of Congress, has been tarnished by prosecutorial misconduct in the case against former Sen. Ted Stevens (R-AK).

“You would hope that the prosecutors are looking very closely at Ensign — looking through all of this trove of e-mails they have,” McGehee said. “This kind of practice of paying hush money is a serious threat to public confidence.”

Still, McGehee worries that Justice won’t rise to the occasion and fight as hard as they need to — even though she’s encouraged by reports of an impending indictment against former Sen. John Edwards (D-NC) in another case of trying to cover-up an extramarital affair.

“[Justice] totally screwed up the Stevens prosecution and they’ve sort of been AWOL,” she said. “Even if you look at Abramoff — they were talking at one point about 25 members being involved and the Justice Department ended up going after one or two. They’ve been pretty much of a limp noodle when it comes to Members of Congress.”