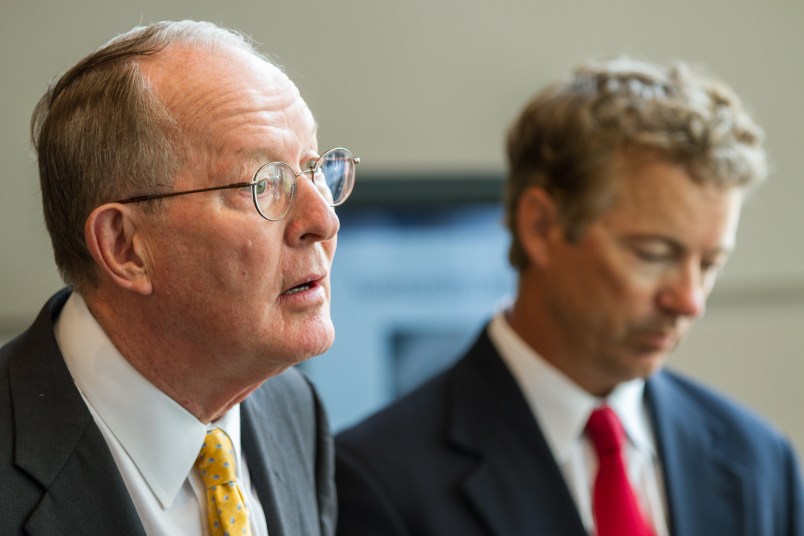

While it hasn’t yet made significant inroads into mainstream D.C. political coverage, Congress’ push to reform No Child Left Behind (NCLB) has continued over the last several weeks. Sen. Lamar Alexander (R-TN), chair of the Senate’s Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee, recently backed away from his first 2015 effort at rewriting the bill and invited committee Democrats to join him at the drafting table.

It isn’t yet clear what will come of this new legislative work. The politics surrounding NCLB remain extremely damning. But it seems that just about everyone in Congress agrees on one thing: The federal government’s role in public education should be weakened in favor of more state flexibility and local control. Above all, most everyone is eager to see the law’s accountability provisions weakened or erased. The current in this direction is so strong that most of D.C.’s education policy community—other than the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights—seem to be taking it as a given.

But as is usually the case, outnumbered, unpopular civil rights crusaders have a way of tickling the guilty consciences of those contentedly riding the waves of conventional wisdom. Which is why—in spite of the Beltway consensus on reducing the federal role in public education—Alexander still had to address the issue at the Brookings Institution earlier this month. Asked to respond to those who worry that his NCLB rewrite won’t retain federal protections for “the most vulnerable children—minority kids, non-English speaking kids, [and] poor kids,” Alexander replied:

In the 70s or 80s I might’ve found that more persuasive, but in the Southern United States, where suddenly we have so many African-American mayors and others on local school boards, and that’s not very persuasive to me. I don’t buy the idea that the only people who cherish children are in the United States Senate or the U.S. Department of Education.

Which is, you know, an answer that’s true in a particularly Southern sort of way. For every effort to curb racism in the region for the last 100 years, there’s been a chorus of folks arguing that they’ve already done enough. Or claiming that folks in Washington “don’t understand” their communities’ needs and/or the region’s unique culture.

Let me put this another way. Sure, there’s some evidence that racism is less prevalent than it was 40 years ago in the South. But that’s an irrelevant answer to concerns that racism still pervades our public institutions. “We’ve improved somewhat” is not a replacement for “We’ve solved our inequity problem.” It’s like saying, “Well, we’re not overtly violent towards minorities as often as we once were, so we can shelve our old protections against systemic racism.” It’s like calling a house finished after raising just three walls—because hey, it looks better than it did before we started.

Aside from that basic logical trouble, there are serious empirical problems with Sen. Alexander’s thinking. If the increasing number of African-American mayors in the South was actually a fair proxy for educational equity, we’d expect to see some data showing that racial parity was arriving in American schools. So let’s check the tape.

Last week, the Department of Education announced that the American high school graduation rate hit a new record high of 81 percent in 2012-2013. But the Schott Foundation simultaneously released a report showing that only 59 percent of African-American males graduated from high school that year. African-Americans in Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Florida and South Carolina all graduated African-American males at rates lagging that deplorably low national average.

There’s more. American schools remain highly segregated by race and class. School funding remains inequitable and tilted towards wealthy students in many states across the country. Minority students are more likely to be assigned inexperienced teachers, and less likely to attend schools offering a robust slate of honors and AP courses. This two-tiered education system starts at the very beginning: 57 percent of black kindergartners attend school in high-poverty classrooms (compared to 5 percent of white kindergartners).

States aren’t the sole cause of all of those ugly stats, of course. But without federal pressure, the track record is extremely, flatly clear: states almost never get around to addressing educational inequity. They drag their feet on implementation (pp. 20–27), in part because they vary widely in their willingness and capacity to follow through on even basic reform efforts (just check the title of Chapter 3 in this old GAO report).

Sure, today’s Washington fetishizes federal education policy flexibility. No one likes the old prescriptive accountability of NCLB. But here’s the rub: As nice as it sounds, flexibility also leaves open the option of ignoring those who most need educational supports. Congress knew that more than a decade ago, when those accountability provisions were crafted with strong bipartisan support. And states’ greatest hits parade on education includes tooth and nail fights to keep the flexibility to maintain segregated schools. And massive funding inequities. And so on.

The federal government, warts and all, remains the strongest force pushing to rectify those shortfalls. Rather than throwing in the towel on NCLB accountability, Congress ought to look for ways to strengthen it.

So if Sen. Alexander wants the country to trust states to do right by minority students, low-income students, English language learners and children who fall into more than one of those categories, it would be nice if he’d offer some reason—or evidence—that anyone else ought to join him.

Conor P. Williams, PhD is a Senior Researcher in New America’s Early Education Initiative. Follow him on Twitter @conorpwilliams. Follow him on Facebook.