On Tuesday, over the course of the day, President Trump called both the Las Vegas massacre and the Hurricane Maria aftermath in Puerto Rico a ‘miracle’. Some of this is simply President Trump’s ingrained weirdness, an uncanny awkwardness rooted in narcissism and a profound failure of empathy. But there’s something more than that. Trump, in his own unique and torrid awfulness, seems more like an intensification of something that predates him. We respond to unimaginable tragedies by deeper and deeper evocations of our own unique bonds of community and sacrifice which should shine through as a point of pride.

Often this celebration through grief focuses on first responders, their sacrifice, heroism and professionalism. This is sensible and appropriate in many ways because police officers and other first responders literally run toward danger while others are fleeing. In certain cases, the particulars of a catastrophe take on a life of their own. The way that hundreds of New York City firefighters died in the collapse of the Twin Towers is an example that comes to mind. 343 firefighters died in a flash when the towers collapsed; 60 police officers died and 8 paramedics. Thousands of other people died as well. But the victims in the building that morning were caught in the wrong place at the wrong time. The firefighters ran into a burning building and paid with their lives.

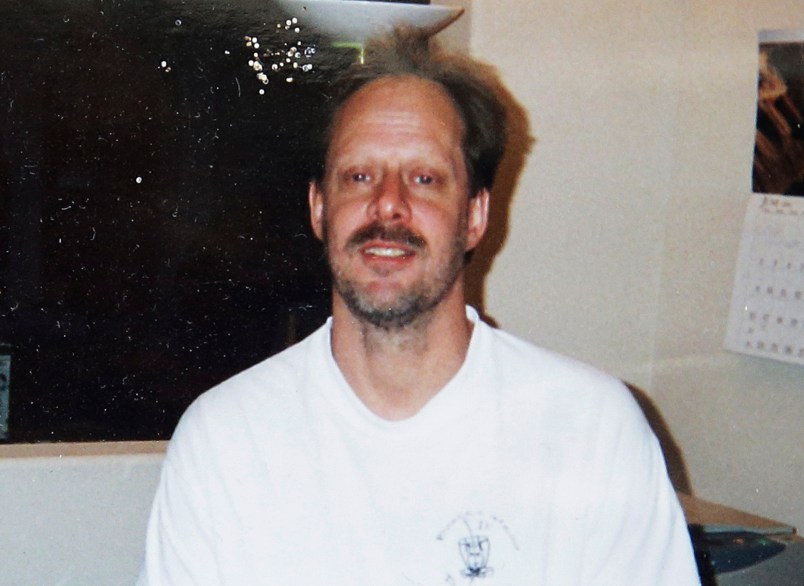

In other cases, heroic and professional work by police officers or other first responders prevent far greater calamities. But in this case all the heroism and professionalism couldn’t stop an almost unimaginable tragedy. The difficulty of the situation from a police point of view is chilling to consider. You have a man hundreds of yards away, firing off hundreds of machine gun rounds into a trapped group of 20,000+ concert goers. It would have been incredibly difficult to piece together precisely where the gunfire was coming from and whether there was one or more shooters. There are multiple high-rise buildings, hundreds of rooms. Current reports suggest that Paddock was able to fire at will for roughly 10 minutes, firing hundreds of rounds into the penned in crowd. Why he stopped when he did is unclear. Police were able to enter the room roughly one hour after the gunfire began.

This was an entirely novel set of facts – sustained automatic gunfire, thousands of targets, hundreds of yards away, 32 flights up into a high-rise. All the valiant professionalism was not able to prevent an almost inconceivable horror. That’s something to sit with and absorb.

The numerous acts of sacrifice, heroism, humanity amidst unspeakable fear and heartbreak were there. But that is really part of the human condition. We are not really so great or exceptional in that regard. What is out of the norm is that these horrors happen here again and again. They do not happen anywhere else. That’s on us. We seem to be using the former to look away from the latter.

The simple fact, especially with gun massacres, is that we take our inability or unwillingness to look clearly at ourselves and transmute it into a mania of self-celebration. As Trump put it in his prepared remarks today: “We struggle for the words to explain to our children how such evil can exist, how there can be such cruelty and suffering. But we cannot be defined by the evil that threatens us or the violence that incites such terror. We are defined by our love, and courage, in the darkest moments what shines most brightly is the goodness that thrives in the hearts of our people.” Later he said “words cannot describe the bravery that the whole world witnessed on Sunday night” and that “a grateful nation” thanked the city’s first responders for their service.

I’ve mentioned elsewhere that Trump routinely stand-ups first responders and police as exemplars of sacrifice, courage and Americanism against non-white protestors or ‘ingrate’ Puerto Ricans. That’s a critical issue. But it’s a separate one. This one is magnified by Trump. But it didn’t start with him.

Massacres like this rarely happen anywhere else in the world. There’s no other country without at least low-level warfare where these massacres are routine. They are routine here in the United States. They have become almost a cliche of early 21st century American culture. We let this happen. We are fierce Jeremiahs about terrorism and gang violence but we’re Ecclesiastes when it comes to mass shootings. It is unknowable, unstoppable. It’s part of something in the human condition we can grieve but never truly understand. Our public sentiments are learned helplessness and evasion.

As I’ve been writing, I’ve wondered whether our reaction to natural disasters is different in kind. We can’t prevent the weather, prevent hurricanes. But of course it’s not quite that simple. We probably are over time making them worse through the change we are bringing to the climate. So perhaps it’s not that different. Do we honor our perseverance because we can’t face our complicity?

I’m not sure they’re the same, whether the moral dynamics and dynamics of evasion are entirely similar. But I’m pretty sure this is the case with the unique-to-America phenomenon of mass shootings. Even our jihadists have ‘gone native’ as the outdated phrase has it, acting out terrorist violence through our own domestic violent American idioms. We are all guilty for these horrors. Our celebration of our greatness seems to be how we look away.